Driva Qele / Stealing Earth: Oral Accounts of the Volcanic Eruption of Nabukelevu (Mt. Washington), Kadavu Island (Fiji), ~2,500 Years Ago

Oral Tradition, 36/1 (2023):63-90

Introduction

Over the past two decades, it has become clear that culturally grounded stories, once uncritically dismissed as myth or legend, often contain information suggesting that they are informed by observations of memorable events, such as coastal inundation, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and meteorite falls (Nunn and Reid 2016; Nunn 2014; Masse 2007; Piccardi and Masse 2007). The principal value for natural scientists of recognizing these stories for what they are lies in the potential extension of detail, beyond that possible from retrodictive scientific enquiry, about the manifestations of these events and their effects on landscapes and their inhabitants. Understanding the empirical basis of these stories also allows insights into the ways in which people once explained such memorable events and how these explanations were conveyed orally, often exaggerated and reworked, across many generations (Nunn 2018; Taggart 2018; Kelly 2015)—a process characterized as “memory crunch” (Barber and Barber 2004).

Stories about volcanic eruptions which are likely to have some empirical basis have been recognized from many parts of the world (Nunn et al. 2019; Nordvig 2019; Riede 2015; Vitaliano 1973). While unquestionably grounded in cultural worldviews and filtered through cultural lenses, the nature of which is key to understanding the probable meanings of these stories, there is enough information within many to allow geologists to identify diagnostic information about particular eruptions. In the Asia-Pacific region, on which the present study focuses, common elements of many such stories include their use of analogues to explain unfamiliar phenomena and their attribution of cause to a supernatural being (like a god, monster, or giant) related directly to the affected peoples (Cashman and Cronin 2008). Many stories also recall plausible details about the eruption, including some unrecognized by scientific study, such as the toxic gas emissions from the c. 7,000-year-old eruption at Kinrara, Australia (Cohen et al. 2017:87-88), and the times when the fractious god Pele chased those who offended her, interpreted as memories of flank lava flows on the island of Hawai’i (Swanson 2008).

The practice of using ancient, culturally filtered narratives to illuminate the nature of past geoscientific phenomena and their impacts is termed “geomythology.” While geomythology remains somewhat radical among the community of natural scientists, it has also received

63

criticism from anthropologists and folklorists who deem its treatment of important questions—such as how “myths” develop from preliterate people’s experiences of catastrophic events—to sometimes be superficial and even perhaps misleading (Nordvig 2021; Henige 2009). These issues are revisited in the Discussion below.

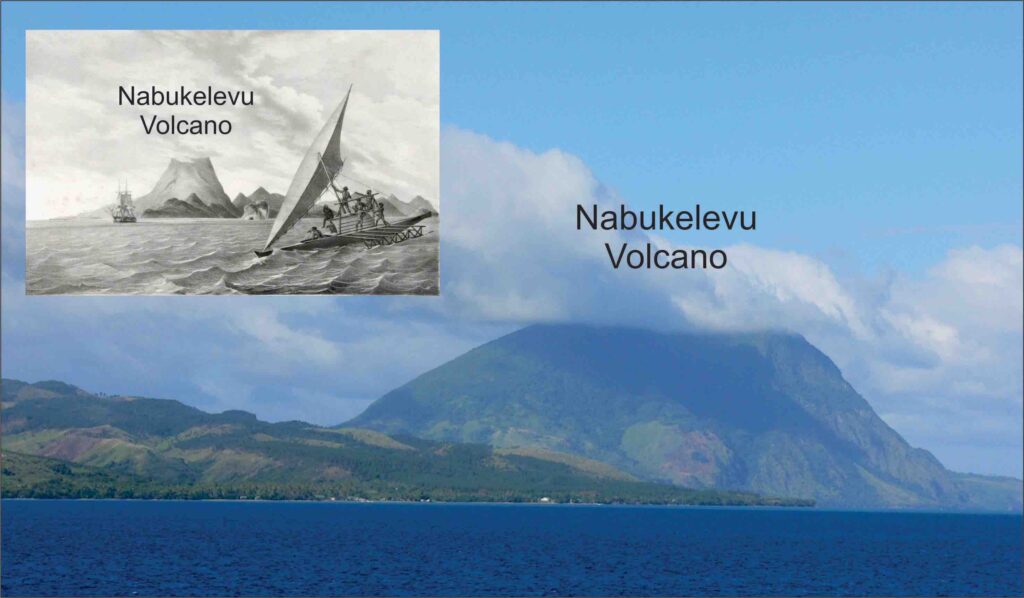

The volcano of Nabukelevu, which dominates the western extremity of elongate Kadavu Island in southern Fiji, erupted at least three times during the three millennia that this archipelago has been occupied by people (Cronin et al. 2004). Stories about an eruption of Nabukelevu, known as Mt. Washington during Fiji’s colonial era, were first written down in the early-twentieth century and remain well known as oral traditions among contemporary Kadavu residents. Analysis of these stories has the potential to explain what happened during this eruption, how people living at the time in different parts of Kadavu rationalized what they saw, and how such stories were encoded in oral tradition and have been sustained since. This study focuses on these questions to reach a deeper understanding of this eruption and its impacts, physical and cognitive, on the people of Kadavu.

Study Area

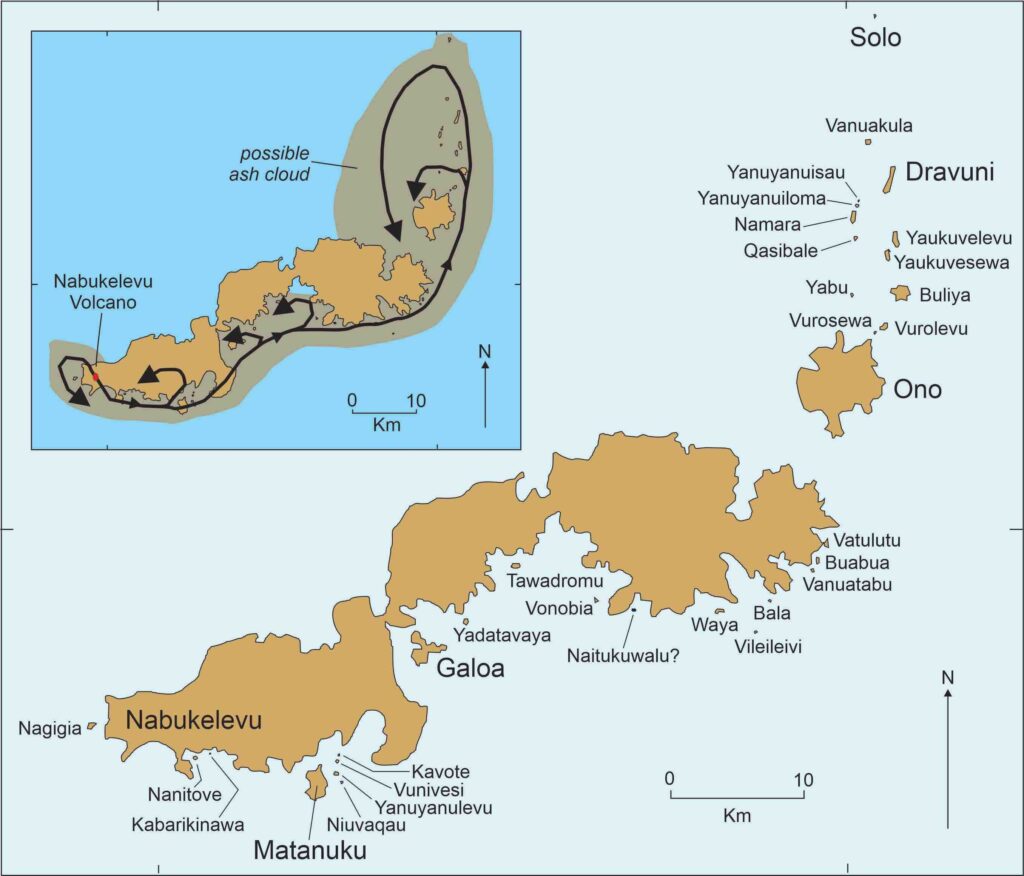

While most of the land area in the Fiji Archipelago (Figure 1A) is volcanic in origin, there has been little volcanic activity since people arrived around 3,000 years ago. Within this period, volcanism has occurred only on Taveuni Island, the latest eruptions perhaps only a few hundred years ago, and at the western end of Kadavu Island, somewhat earlier (Cronin and Neall 2001; Nunn 1998).

People arrived in the Fiji Islands around 850 BCE, probably settling first at Bourewa and Qoqo in what is now the southwest part of Viti Levu, the largest island in the group (Nunn and Petchey 2013; Nunn et al. 2004). Fragments of their uniquely decorated pottery show they had dispersed to most parts of the archipelago by 550 BCE. The large yet isolated Kadavu group in the south of Fiji has no unambiguous record of occupation by these early (Lapita) people, although it would be surprising had they not reached it (Clark and Anderson 2009); mineralogically distinct pottery from this period found on the island of Moturiki in central Fiji is likely to have been manufactured on Kadavu, although where is unknown (Kumar et al. 2021).

Kadavu is the name used for the main island of the Kadavu group (Figure 1B), which formed from a series of volcanoes, oldest in the northeast and youngest in the southwest, resulting from proximal plate convergence along an ocean trench to the south of the main island (Nunn 1998). Kadavu soils are fertile and well watered, underwriting food production that today sustains a population of approximately 10,900 people living in sixty coastal settlements. Little is known about the early (pre-European contact in 1643 CE1) history of Kadavu (Burley and Balenaivalu 2012), although it became an important transit site for trans-Pacific shipping in the 1870s (Steel 2016).

1 Abel Tasman sailed through northeast Fiji in 1643, but James Cook seems to have made first contact when he landed on Vatoa Island in 1774. Sustained European contact began a few decades later.

64

65

For this study, the main island of Kadavu (and smaller islands nearby) was targeted both because of the conspicuous form of the Nabukelevu volcano (see Figure 2) but also because of the authors’ pre-knowledge of several stories about its eruption. Fieldwork for this study was conducted on Kadavu on two occasions in 2019 by the three lead authors. Original stories likely to recall a volcanic eruption were collected from several places there, notably the villages of Nabukelevuira at the foot of the volcano and that of Waisomo on Ono Island, a key location in most stories.

Nabukelevu Stories

The common detail in almost all oral stories recalling the Nabukelevu eruption is that it involved an interaction between two gods (vu or supernatural beings) named Tanovo (from Ono Island) and Tautaumolau (from Nabukelevu). Names/spellings differ between stories, but these are considered the most authentic written versions. The essence of the story is that Tanovo travels from his home on Ono to Nabukelevu, where Tautaumolau has built a huge mountain (Figure 2). Angered by or envying Tautaumolau, Tanovo starts to dig material from the top of the mountain but is caught by Tautaumolau. Carrying woven baskets full of this material, Tanovo is chased by Tautaumolau through the sky along the elongate axis of the Kadavu group, dropping material in several places to create islands. At one point, one of these gods throws a spear at the other, creating a hole in a cliff (see Figure 4A). Finally, the two gods resolve their dispute.2

2 None of the stories state who won the contest, possibly a memory of a truce that has been honored since.

66

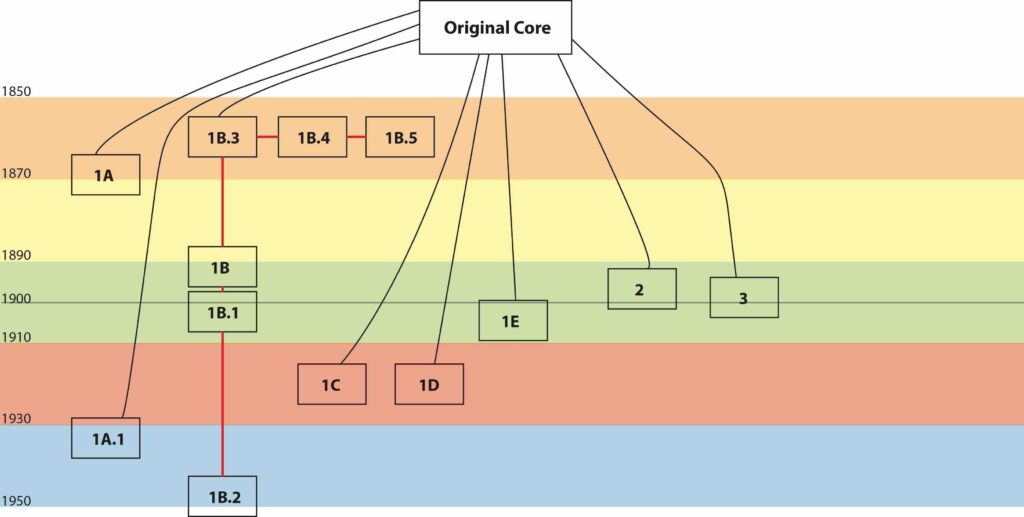

There are several known variations of this story which are considered important to understanding its evolution. These variations, sources of which are shown in Figure 1C and the proposed lineage of which is illustrated in Figure 3 below, are summarized in the following subsections: the first dealing with written (published and manuscript) versions, which represent transcribed oral traditions, the second with original oral traditions collected in 2019.

Recently Transcribed Versions of the Nabukelevu Story

The earliest written versions of this story date from the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries (Beauclerc 1909; Deane 1909) and directly informed later versions (Nunn 1999; Riesenfeld 1950). These stories collected by settlers, probably independently of each other, are factual and likely to have been rendered verbatim. A slightly different version was published in 1965, probably obtained from a separate oral source given that the author was a mission teacher on Kadavu, as part of a compilation of stories (Hames 1960). This version of the story appears to have informed a 1971 Fiji Education Department booklet (Hamilton and Mansfield 1971). A third written version contributed to a compilation of Kadavu stories by high school student Sokoveti Lasini a decade later (Veramu 1981). Another version was published in 2017 by Kaliopate Tavola, Fiji’s former Minister for Foreign Affairs (Tavola and Tavola 2017), published

67

more fully on his website (https://kaidravuni.com) and told more fully during discussions at the Fiji Museum in January, 2019.

There are three versions of the story in the Carey Papers, an unbound, unpublished collection of notes and observations by the students of Reverend Jesse Carey, written in Fijian, dated to the 1860s, and stored at the Mitchell Library, Sydney. These versions are by Patimio Nasorowale, Joeli Nau, and Leonaitasi Tuileva, Methodist students who were being trained at the Richmond Missionary College on Kadavu and who were invited to contribute as part of an intentional effort by Carey to compile ancient Fijian stories before they became forgotten.

Extant Oral Versions of the Nabukelevu Story

In January, 2019, three versions of the story were collected from persons in the Kadavu group of islands who were identified by community leaders as those who best knew the old stories. One version was collected from Ratu Petero Uluinaceva in Waisomo Village (Ono Island), another from Ratu Eveli Yalanabai in Nabukelevuira Village at the foot of the Nabukelevu Volcano, and a third, more abbreviated, version from Bulou Taraivini Likutotoka in Vabea Village (Ono Island). All interviews were in one or more dialects of Fijian, that of Ono differing significantly from that of Nabukelevuira, and collected in culturally appropriate contexts following proper protocols. It is of interest to note that many younger community members gathered to listen to these stories on these occasions, which were filmed by Jerry Veisa of the Fiji Museum. A final oral version of the Nabukelevu story comes from Ravitaki Village (Kadavu) and was obtained in Australia from Taniela (Dan) Bolea, a former Ravitaki resident.

Results

By analyzing the key elements of what we consider original (not repeated) stories, this section identifies thirteen distinct versions of the Nabukelevu story. Each version is assigned a number reflecting its proposed lineage, illustrated in Figure 3 and based on commonalities and differences identified through content analysis, summarized in the remainder of this section, and through the names of particular islands said to have been created by soil falling from Tanovo’s baskets (Table 1).

68

| Version | Islands off mainland Kadavu | Astrolabe Islands |

| 1A | Galoa | Bulia, Dravuni |

| 1B | Dravuni, Solo | |

| 1B.1 and 1B.3 | Nagigia, Kabarikinawa, Nanitove, Matanuku, Niuvaqau, Vaboa, Galoa, Yadatavaya, Tawadromu, Vanobia, Naitukuwalu, Waya, Vileileivi, Bala, Vanuatabu, Buabua, Vatulutu | Vurosewa, Vurolevu, Yabu, Buliya, Yaukuvesewa (Yaukuvelailai), Yaukuvelevu, Qasibale, Namara, Yanuyanuioma, Yanuyanuisau, Dravuni, Vanuakula, Solo |

| 1B.2 | Dravuni, Solo | |

| 1D | Yaukuve, Bulia, Dravuni | |

| 1E | Matanuku, Galoa, Yanuyanulevu, Niuvaqau, Kavote, Vunivesi |

|

| 2 | Ono, Dravuni, Buliya, Vanuakula, Qasibale, Yaukuve, Solo |

|

| 3 | Qasibale |

Version 1 is that which involves all key elements, as outlined above, while Version 2 is distinct because there is no rivalry between the two gods, and Version 3 is unique because there is dispute but no explicit mention of a chase.

An early expression of Version 1A is that of Beauclerc (1909), who says he heard the story in 1871. It states that Tanovo, accustomed to enjoying the sunsets from his home on Ono

69

Island, discovered one night that a mountain had appeared at Nabukelevu to block his view,3 so he decided to travel there, pull down the mountain, and create new islands. Tautaumolau caught him in the act, so Tanovo hid under the sea with his baskets of earth, but Tautaumolau drank the ocean to expose him. Chased by Tautaumolau, Tanovo then unloaded his baskets of earth, forming islands (see Figure 5). Reaching the passage in the reef north of Ono, he turned south again until, exhausted, he hid under a rock at which Tautaumolau launched his spear, piercing it (see Figure 4A).

Beauclerc admits he may have forgotten some key details; we suggest that his identification of Dravuni as the island first formed when Tanovo was being chased and Galoa as the one next formed is an example of memory lapse, because all other variants of Version 1 have these islands in a more plausible order (see Table 1); Galoa is far closer to Nabukelevu Volcano than Dravuni.4 Beauclerc also mentions that while Tanovo is still on Ono (before traveling to Nabukelevu), he declares his intention to create new islands, a detail not found in other stories, where this is explained as an accidental consequence of Tanovo being surprised and chased by Tautaumolau.

Similar to this version is the oral account by Ratu Petero Uluinaceva (Version 1A.1), which, he stated, is essentially that which his uncle would have heard towards the end of the 1940s. Like Version 1A, this rendition of the story focuses on the enjoyment that Tanovo got every afternoon from watching the sun set from Ono Island—and the anger he felt when his view of the sunset became obstructed by a mountain (Nabukelevu5) raised to the southwest, as it does still in November-December:

For us who have heard the legend, we believe the sunset that was linked to Tautaumolau would have been around November/December. Indeed the best time for us here in this village to watch the sunset is around that time. The sunset then begins to move in the other direction so that by May, sunlight is shorter, the weather is cooler as the sun is further away from us. That is why when we talk about this story we think it must have occurred during the November/December period when sunsets are always really beautiful.6

3 Field surveys in 2019 show that Nabukelevu is indeed visible from several of the highest peaks on Ono Island.

4 Beauclerc also appears to have forgotten the names of the gods in the story he was told almost fifty years earlier, calling them by default Ra Ono (Tanovo) and Ra Buke (Tautaumolau).

5 The name “Nabukelevu” means “the great yam mound,” a familiar analogy to people in Kadavu, past and present.

6 Ratu Petero spoke in Standard Fijian (Bauan). In the original,

Ia na ka keimami nanuma keimami na rogoca na italanoa ni vanua e tiko mai kina na ikarua ni vu qo o Teiteimolau mai Nabukelevu, kevaka ena dromu kina na siga, ena dromu tiko ena maliwa ni Noveba kei na Diseba, baleta na vanua e tiko kina o Nabukelevu—kevaka e via sarava tiko o koya ni via dromu na—ia na gauna vinaka duadua vei keimami na koro qo me keimami sarava na matanisiga ni keimami sarava ni sa dromu na yasana qo. Io sa dromu tiko i yasana qo. Io o koya ni qai lesu tale tiko me yacova na vula o Me sa dau lekaleka ga na lako ni matanisiga, sa dau vula i batabata vei keimami. Sa batabata na draki, na matanisiga sa yawa mai vei keimami. Sa qai dau cawiri cake mai o koya, na vula o Diseba sa dromu sara i yasana qo. Ia na vakasama keimami dau veitalanoataki koya tiko kina na vu qo, o koya na ka e yaco oqo baleta na mua ni yabaki—Noveba ki na Diseba—na vanua ya e dau dromu kina valekaleka saraga, dau rairai vinaka talega vei keimami na matanisiga ni dromu valekaleka saraga i ke.

70

A unique element of Version 1A.1 is that the mountain of Nabukelevu had existed for some time before Tanovo decided to go and lower it. Version 1A.1 recalls how Tanovo

set off early while it was still dark, as he wanted to get to Nabukelevu and commit his treacherous deed and be out of there before daylight. He took with him a few giant baskets of plaited coconut fronds. Then he proceeded to dig the earth . . . but as he was digging, the dawn broke. Tautaumolau had by then arisen and promptly spotted Tanovo’s furtive activities. Tanovo fled, wanting to get to the top-end of Kadavu [its northeast extremity] before Tautaumolau could catch him. The furious chase got as far as the shores of Nakasaleka [district] when Tautaumolau got close enough and threw a spear at Tanovo. But it missed and instead pierced a large boulder and made a clean hole right through it [shown in Figure 4A].7

According to this version, Tanovo became increasingly aware of the danger from his furious pursuer, so he headed for the big reef (Cakaulevu or Great Astrolabe Reef) along which he traveled for some distance before turning left (west) and heading towards his home on Ono Island where he felt he would be safer. Around the same time, aware that the sunrise was illuminating him and his actions, Tautaumolau realized he was isolated, an aggressor in a foreign territory.

This version of the story, one presumably nurtured by the Ono people, does not discuss the conflict between Tanovo and Tautaumolau further, but continues with an explanation of how Tanovo has become embodied in the landscape of Ono Island:

To this day there are two streams below Tanovo’s abode called Mata i Tanovo [meaning “the eyes of Tanovo” or “the face of Tanovo”] and if you want to go there, you will climb up one hill called Duru i Tanovo [the knee of Tanovo] and like a knee, you go up one side and descend down the other.8

While other versions of this story often involve a reversal of roles in the chase, the 1A versions are the only ones in which it is only ever Tautaumolau chasing Tanovo.

7 In the original,

Sa dua na siga sa baci raica tale toka o koya sa baci lai buawa vua na matanisiga sa lai tabogo, sa mani nanuma o koya, “Au sa na lako mada meu laki kelia laivi na delana qo, meu na kelia laivi me biu laivi i wai, me rawa ni dromu ga na matanisiga, au sa sarava.” Ia e na gauna qo kevaka iko via raica na delana oya, iko na toso ga vakalailai i yasana qo sa na raici koya na delana ni sa basika. Sa mani gole sobu tu o koya dua na mataka lailai, qai tukuna o koya, “Me se mataka caca—‘o yau na gauna meu butakoca kina na ka qo me se buto tiko ga na vanua meu sa lesu tale mai. Me qai ka ni mataka na vanua, meu sa yali mai.” Sa mani kauta o koya e vica vata na isu lelevu sa qai laki kelia kina o koya na qele. O koya na qele ya e sega ni kelia me biuta laivi, o koya qai kauta mai. Qai kauta cake tiko mai o koya. Na gauna saraga e kelikeli oti ga sa lako talega mai na nona itokani o Teiteimolau, qai raici koya. Qai sasaga cake mai o koya i muana i cake i Kadavu ni se bera ni tarai koya o Teiteimolau. Nodrau sa veicemuri voli mai ya, qai yaco mai na baravi i Nakasaleka qai cokai koya rawa kina o Teiteimolau—qai cala na icoka ya. Kena cala ya qai lauta e dua na ucunivatu, se tiko ga qo, se qara vinaka saratu ga mai yasana kadua ki yasana kadua. E rawa ni da kele ga kina vaqo da tara na qara ya ni sa basika i yasana kadua.

8 In the original,

Ia na gauna qo, na delana dau tokatoka kina ya, e tiko e ra e rua na mataniwai, se yacana tiko ga o Mata i Tanovo. Tiko i ra e na gauna qo. Ia kevaka eda taubale i kea, e dua ga na delana dou na lai cabeta, na yacana tikoga Duru i Tanovo. Se wili tikoga vaka duruna ga—vaka ga na duru—lako ga vaqo, lai siro tale i yasana kadua.

71

All five Version 1B stories have the role of Tautaumolau as pursuer reversed when the pair reaches some northern point in the Astrolabe Islands and Tanovo starts pursuing Tautaumolau, perhaps because Tanovo felt empowered by being on his home territory. All 1B stories have the common detail that Tanovo was jealous of Tautaumolau because the latter’s hilltop home was higher than his, so he decided to try and lower it.9

It is possible that the earliest of these stories (Version 1B) is that of Deane (1909), who states that this is a story he “heard previously,” although exactly when is uncertain; it is far more detailed and contextualized than that of Beauclerc (see above). He states that Tanovo and Tautaumolau are vu, ancestor figures whose deeds are invariably aggrandized and their legacy amplified, and who often pass into myth as protectors of clan groups, dedicated to their survival, alert to threats. Deane notes that both these vu are well known in Kadavu and that there are innumerable landforms associated with each. A distinct element of this version is that Tautaumolau was joined in his pursuit of Tanovo by the vu of nearby Tavuki and Yawe. As the pursuer-pursued roles are reversed, it is Tautaumolau who hides beneath the sea near Tiliva, then above Nakasaleka (perhaps Kavala Bay), and finally behind a headland that is pierced by Tanovo’s spear (shown in Figure 4A).

Similar to this are the written and oral accounts of Kaliopate Tavola (Version 1B.1), born and raised on Dravuni Island, whose mission is to preserve such traditions and understand their significance. He first heard the Nabukelevu story in the late 1940s or early 1950s from his grandfather and others who stated they he had heard it first in the mid 1890s. The key difference here is that, after Tanovo dropped some of the earth from the baskets he had been carrying while fleeing Tautaumolau, Tanovo was “greatly relieved by disposing of his load. He became reenergized and it was written over all his face.” This allows Tanovo to become the pursuer rather than the pursued, a defining element of the 1B stories. Version 1B.1 has considerable detail about the route of the chase and the islands formed by the “soil” dropped from Tanovo’s baskets.10 After the pursuer becomes the pursued, this version of the story also has Tautaumolau hiding in the “deep sea” at Nakasaleka whereupon Tanovo drinks all the water to reveal him, then hiding behind a huge rock at which Tanovo throws his “stick” to form a hole. Finally, Tautaumolau heads home to Nabukelevu.

The story (Version 1B.2) told in Riesenfeld’s (1950) tome about the megalithic culture of Melanesia refers to Deane as a primary source but adds a few minor details, unlikely to have been obtained firsthand. Key among these is that the chase on mainland Kadavu is partly along its southern reef and partly along its spirit path (1950:590).

The fourth version of this story (Version 1B.3) is that by Joeli Nau, a Tongan (not Fijian)

9 In the past, many Fijians on high volcanic islands like those in the Kadavu group occupied mountaintop hillforts (koronivalu). We note the report of Titian Ramsay Peale, chief naturalist on the United States Exploring Expedition (1838-42), who saw on Kadavu “the remains of forts, consisting of stone walls 4 feet thick and about the same height surrounded by a dry ditch. They are always on the crests of hills” (Poesch 1961:174).

10 In order from the start to the end of the chase, these are Nagigia, then islands along Babaceva: Kabarikinawa, Nanitove, Matanuku, Niuvaqau and two smaller ones nearby, Vaboa, Galoa, Yadatavaya, Tawadromu, Vanobia, Naitukuwalu, Waya, Veilailaivi, Bala, Vanuatabu, Buabua, Vatulutu, Vurosewa, Vurolevu, Yabu and Buliya and then Yaukuvesewa (Yaukuvelailai), Yaukuvelevu, Qasibale, Namara, Yanuyanuioma, Yanuyanuisau, thence Dravuni and Vanuakula, and finally isolated Solo.

72

Methodist minister who studied at the training institute in Richmond on Kadavu Island and married a local woman. We know he traveled to Ono Island at some point and that he had a keen interest in recording and understanding such traditions. The close similarity between this version of the Nabukelevu story and that of Deane suggests they probably originated from the same source, some time during the mid-nineteenth century.

Another version of this story (Version 1B.4) is that told by Patimio Nasorowale, a Fijian “native teacher,” trained in Richmond, who claims that Tanovo was the common ancestor for all people in Kadavu. Since this is not a detail found in any other version, it could be an inference added by an outsider unfamiliar with Kadavu culture, although Tanovo is said elsewhere to be the common ancestor (vu) for many villages on both Kadavu and Ono islands.11 Distinct in Version 1B.4 is that after throwing his spear at Tautaumolau, Tanovo returns to Ono.

The final version of this story (Version 1B.5) is by Leonaitasi Tuileva, another Richmond-trained “native teacher,” who also states that the whole of Kadavu was once subject to Ono, which may explain why Tanovo (the vu of Ono) was so irked by the actions of upstart Tautaumolau. This version states that it was only after the attempted spearing of Tautaumolau by Tanovo that the former tried to hide beneath the ocean.

The binding element of these six 1B versions is the reversal of roles in the chase around Kadavu, something that happened only after Tanovo reached the end of the Kadavu island chain on the north side of the Solo Lagoon (see Figure 5). In 1B and 1B.2, this point inspires the cry, “turn ye sons of Ono”;12 in 1B.3, “our masi [barkcloth loincloths], of us people of Ono, are wet, let’s dry them in the sun”;13 and in 1B.4, the more challenging call of Tanovo to his rival, “See, you and I are both champions! Today we will both die!”14

Version 1C was told by schoolgirl Sokoveti Lasini from Yale on Kadavu about 1980 and was reportedly that told her by her grandfather, who probably heard it in the 1920s from one of his elders. The key distinct elements are that Tautaumolau almost caught Tanovo in Nakasaleka district and that the soil from his buckets formed only the small islands of the Ono district.

Another story (Version 1D) was told in 2019 by Taraivini Likutotoka from Vabea Village on Ono Island who, born at Narikoso on the same island, heard this story from her grandmother who had listened to it as a child, possibly in the 1920s. While key elements of the narrative are the same, the chase ends when Tanovo, returned to Ono, pushes this island away from mainland Kadavu using his foot. The footprint is visible in the cliffs (see Figure 4B).

Taniela Bolea from Ravitaki on Kadavu told Version 1E of this story, which he heard from his granduncle Kalaveti Cawa from Matanuku Island, who had heard it as a child, possibly around the year 1906. While admitting to being uncertain about some of the details, Bolea told a version of the story similar to others within the broader category of Version 1. The key difference

11 Manuscript by E. Rokowaqa, Ai tukutuku kei Viti (Suva, c. 1937).

12 In the original Bauan language, “Nī vuki na luvei Ono.”

13 In the manuscript original, “Sa suasua na noda masi na kai Ono, da raki mada.”

14 In the manuscript original, “Ia, daru sa tagane vata ga! Edaidai daru sa dui mate!”

73

is that the only islands “formed” by soil from Tanovo’s baskets are those close to Ravitaki Bay, suggesting a localization of the narrative.15

While working as a missionary and schoolteacher at Jioma on Kadavu in 1942, Inez Hames was told Version 2 of this story by an elderly man (unnamed) who we infer would have heard it as a child in the 1890s. This version of the story is more sympathetic to Tautaumolau than most others. It states that the two gods were peaceably drinking kava (yaqona) together when Tautaumolau suggested removing part of mountainous Nabukelevu and putting it in the sea to extend his lands. Tanovo did not like this idea, so he decided to dig Nabukelevu himself and use the soil for his own purposes. In the ensuing chase, it is Tautaumolau who throws the spear at Tanovo. The soil is dropped to form Ono itself (as well as other islands), which is where the story ends.

The final version of this story (Version 3) was told in 2019 by ninety-year-old Ratu Eveli Yalanabai of Nabukelevuira Village at the foot of Nabukelevu mountain. Renowned as a custodian of traditional stories, Yalanabau heard this story from his parents, who had heard it as children, probably in the first decade of the twentieth century. In this version, Tanovo and Tautaumolau are kin. Ratu Eveli states that the story is

. . . about the bargain between these two, the god of Ono [Tanovo] and the god from here [Tautaumolau]. This transaction started to become a bit difficult especially as the god of Ono became strident. He said, “I am going to scoop up this earth.” The god of Nabukelevu said, “That’s up to you. Our close kinship will not be erased away, irrespective.” So the god of Ono scooped up earth and filled his coconut frond basket, but clumps of earth started to fall through the gaps in the basket and formed those small islands. While the god of Ono was carrying his basket, the god of Nabukelevu was watching him from Ului Nabukelevu [the summit of Nabukelevu]. He got a stick and threw it at the god of Ono and caused the basket to burst and ended up forming all those islands in Ono.16

Analysis

Like many similar stories, it is likely that the Nabukelevu story analyzed here is built on contemporary cultural foundations from syncretized memories of distinct events, notably (a) a volcanic eruption (at Nabukelevu) that built up a mountain which obstructed views towards the southwest for people elsewhere in the Kadavu group (especially Ono Island) and (b) rivalry

15 These islands include all those in Ravitaki Bay as well as (in order) Matanuku, Galoa, Yanuyanulevu, Niuvaqau, Kavote, and Vunivesi.

16 Ratu Eveli spoke in the local Nabukelevu dialect. In the original,

Xa meri na nodru vixerexerei ga xedruxa xea, xedruxa na vu mai Ono vataxei na vu ga i e. Sa xora meri vani qai mai dredre valailai, vani dredre valailai na vixerexerei meri. Sa xora ga meri sa qai mani vaqaqa toxa na vu mai Ono. Xora ga vani xea sa qai xaia vani xea, “Olrait au sa luxuta na qele. Au sa luxuta na qele.” “Io vatau vi ixo, vani o sa via luxuta na qele, nodaru viwexani tabu rawa ni taqusi, toxa dredre ga nodu viwexani.” Sa qai luxuta xeya. Luxuta na qele meri qai vatawana i nona vesavesa, qai se qera yarayara jiko na qele. Na jiko ni yanuyanu lalai xea, ga meri na qele. Sa qai tube jixo na vesavesa xea me laxo jixo, sa qai toxa mai Ului Nabuxelevu na vu xea. Qai taura na i xolo qai xolota, xa se qera tu xe meri na viyanuyanu xa dra tu mai Ono meri, meri na xena italanoa. Xia gena xa dra tu xe na viyanuyanu mai Ono meri.

74

between two groups of people in the Kadavu islands which involved aggressive encounters in key places. Also of note is that stories which originated in the western part of Kadavu, closer to Nabukelevu, understandably privilege the views and histories of the people living there, while the stories from the other end of the islands, around Ono, tend to privilege the views and histories of local residents.

This section is divided into two main parts. The first looks at how analysis of selected elements of the narratives allows insights into the relationship between Tanovo and Tautaumolau, where they lived, and how and why particular landforms may have become linked to the stories. The second identifies those common elements in the narratives that are likely to recall the manifestations of volcanic activity, something which allows a likely age for the story to be proposed.

Narrative Analysis

Most versions of the Nabukelevu story collected do not identify the preexisting relationship between its two protagonists, Tanovo and Tautaumolau. Three versions explicitly identify rivalry (Versions 1B, 1B.1, and 1D), while two identify friendship or kinship (Versions 2 and 3). Given the geography of sources shown in Figure 1B, it would be premature to try to analyze these narrative traits other than to note that two versions asserting rivalry come from Ono Island while one involving kinship comes from Nabukelevu.

In all versions of this story except one, the god Tanovo is said to live on the island of Ono; the sole exception is Version 2, in which this island is created by soil falling from Tanovo’s baskets, so it is stated that he lived originally somewhere on the eastern Kadavu mainland, possibly a default inference. In all other versions, where specified, the stronghold of Tanovo on Ono Island is said to have been at either Qilai Tagane (1B), Uluisolo (1B.1), Ului Ono (1B.5), or in the forest (1C). Recent surveys of Ono Island (Nunn et al. 2022) show that evidence for fortified hilltop settlement exists at Qilai Tagane and Uluisolo; no mountain known as Ului Ono is known to the present inhabitants. From both Qilai Tagane and Uluisolo, it is possible to see Nabukelevu Volcano, so it is plausible to suppose it once blocked the view of the sunset. Tautaumolau inhabits Nabukelevu mountain in most versions of the story, although no signs of former occupation have been found there to date by the researchers.17 In versions 1B.1 and 1B.3, Tautaumolau occupies a coral reef named Vunilagi (unlocated) offshore.

While there are numerous aspects of the stories that suggest they recall volcanic activity at Nabukelevu (see following section), there are other aspects that link to particular landforms. The analyses of these links might inform our understanding of the evolution of the story and the ways in which elements of culturally grounded narratives become anchored to place.

All versions of the story involve one god throwing a stick/spear at the other, creating a hole in a cliffed headland. This exists (name unknown) on the north coast of the Kadavu

17 Sometime in the mid-twentieth century, the Reverend Alan Tippett visited Naborua, a hillfort on the flanks of Nabukelevu Volcano. He explained (1958:147) that three ridges stretched out from the mountain

like the buttress roots of rain-forest trees, narrow with blunt ends and a precipice on each side. The fortress was perched on the central ridge. Its only path led along the mountainside, very narrow so that approach had to be in single file. The fort had a death drop on all sides . . . . [T]he place they told me had never been taken. I don’t wonder.

75

mainland, across from southern Ono (see Figure 1A), and is shown in Figure 4A. If its formation predated human arrival in Kadavu around 3,000 years ago, this landform thus provides an example of a fictional detail likely to have been added to a narrative to anchor it to place and remind local residents of it. Similar memory aids have been used in other oral cultures to prevent loss of traditional knowledge, including culture-defining stories of this kind (Kelly 2015). Yet it is also possible that this archway (“hole”) formed during the period of human occupation of these islands, possibly as a result of ground tremors during an episode of Nabukelevu volcanism.

Similar arguments are applicable to the “footprint” of Tanovo, mentioned in all six Versions 1B, where he is said to have placed his foot in order to push his island of Ono away from the Kadavu mainland after his conflict with Tautaumolau. Shown in Figure 4B, visually interpreted according to the directions of local residents, this feature may postdate the arrival of people in Kadavu, even conceivably having occurred at the same time as Nabukelevu volcanism, perhaps because of earth tremors or tsunami impact. Alternatively, it may simply represent a collapse of the cliff at this location that created a footprint-like feature which then became part of the story.

Links to Volcanism

Numerous elements of the stories make it likely that they incorporate memories of volcanic activity at Nabukelevu (Cronin et al. 2004). Discussed in separate subsections below, these are the scooping-out of earth from Nabukelevu by Tanovo (Element a), the inferred initial confrontation at Nabukelevu between Tanovo and Tautaumolau (Element b), the chase along the island chain and back (Element c), the formation of islands through the dropping of soil from Tanovo’s bags (Element d), and the hiding of one god beneath the ocean and the drinking of the ocean by the other to reveal him (Element e).

76

a. Scooping-Out of Earth

While most versions of the story do not mention where Tanovo removed “soil” from Nabukelevu, Versions 1B.1 and 1B.2 (and many anecdotal observations from local residents) mention that material was scooped from the top of the mountain, which is why it has its characteristic saucer shape (see inset, Figure 2); Version 2 mentions a “hole” (perhaps a hollow) in the top of the mountain. This landform represents the summit crater, similar to that found at the top of many young volcanoes. In the case of Nabukelevu, this crater may have formed only after/during an eruption, so it may be a narrative detail that featured in the original version of the story, shortly after the event to which it refers.

b. Initial Confrontation

Few stories have much detail about the nature of the initial confrontation between Tanovo and Tautaumolau at the top of Nabukelevu, although some talk of Tanovo being surprised by his rival/friend. In Version 1A, the baskets into which Tanovo has been scooping earth from Nabukelevu are emptied before the chase begins—a possible recollection of the flank landsliding likely to have accompanied volcanic activity18—but in all other versions that involve a chase, Tanovo lifts these baskets of earth and takes them with him as he flees from Tautaumolau.

c. The Chase

The geographical route taken by the two gods as they flew (or perhaps ran) varies considerably between stories, sometimes being mostly on land, sometimes offshore, dropping material that created islands. It may be that the routes described in the earliest versions of the story did in fact trace the progress of the eruption (ash) cloud from Nabukelevu (observed from different places), but it seems implausible to us to suppose that modern versions of the story would necessarily be as accurate. Details of this are notoriously liable to modification, especially to incorporate places that have risen in importance and, conversely, to jettison places that lose status. For this reason, we attempt no analysis of the precise routes, yet we note that the overall direction—on which almost all versions agree—of the chase is similar. This involves a chase along the south side of the main island (and islands/reefs offshore) which ends in the Astrolabe Islands at the other end of the Kadavu chain. Whether it is Ono or Dravuni or Solo where the chase ends seems less important than the fact that it did end and—as all versions agree—it then reversed and returned to somewhere on the north side of Nakasaleka District.

It seems plausible to suppose this to be a recollection of the direction of an ash plume (perhaps not the only one) from Nabukelevu driving east along the Kadavu chain until, losing strength in the Astrolabe Islands, the wind starts to blow it back south (or southwest). A change in wind direction is not necessary, for the waning of eruption vigor and plume height would entail ash being transported less far from Nabukelevu, giving the impression to observers of the ash cloud traveling back to the southwest. In either scenario, such an ash plume would have been

18 A 5.3 magnitude earthquake shook Nabukelevu on October 21, 2019, and caused numerous landslides.

77

visible to people on the ground, it would have been smelt by them, and it would have made their eyes sting. Perhaps there were no toxic gases present in the plume, for this memorable detail would likely have featured in oral traditions, as it does for the c. 7,000-year-old eruption at Kinrara in Australia (Cohen et al. 2017:87-88).

d. Island Formation

Almost all versions of the story talk about baskets of soil being emptied, accidentally or deliberately, along the outbound route of the chase between Nabukelevu and the Astrolabe Islands. While accepting that the same reasons to treat this information cautiously as we cited for ignoring precise details of the route of the chase may apply here, there are clues from both place-names and geology that supply additional information to assess this information. For this reason, we look at those nine stories that have details specifying which islands were created by the soil falling from Tanovo’s baskets, summarized in Table 1.

The locations of these islands are shown in Figure 5 and, if they approximate the route along which an ash (fine tephra) plume/cloud formed and moved, then a plausible reconstruction is shown in the inset of this figure. All accounts of the chase, as well as the order in which offshore islands are said to have formed, imply that the ash cloud moved along the south side of the main island and then turned back south somewhere north of Ono Island.

78

It is important not to take literally the detail in many stories that these small offshore islands actually formed during the eruption. This may well be a default position adopted by storytellers, otherwise at a loss to explain the presence of such islands and wishing to strengthen the credibility of their narrative by linking their presence to it. It is much more likely that “formation” in the stories actually means that these islands were built up, that material from the sky was dropped on their surfaces, as was the case for similar stories in neighboring Tonga (Taylor 1995). Closer to Nabukelevu, this material may well have included larger particles (lapilli); farther away it is likely to have been exclusively finer material (ash). This may be recalled in the name of the island Dravuni, in Fijian most likely meaning “ash” in this context, which is a bedrock (breccia and lava) island on which ash might have fallen at the time Nabukelevu erupted. Perhaps owing to the high rainfall in this part of Fiji and the regular incidence of tropical cyclones (hurricanes), no ash deposits dating from Nabukelevu have been found in any islands of the northeast Kadavu group.

Insights into the effects of this eruption can also be gleaned from some of the other island names shown in Figure 5. Of particular interest is the island of Galoa (“sunken place”) that may have been named after it sunk abruptly during this event, perhaps as a consequence of a flank landslide or coseismic subsidence, either of which could conceivably have occurred here at the time. Sinking also features in the name of Tawadromu (“sunken [Pometia] tree”) and may be implicated in the name of Kabarikinawa (“floating Kabariki [village]”), perhaps signifying an area of populated land washed out to sea. The names of all three places may also derive from the impact of a tsunami (see below).

e. Hiding under the Sea

At one point, either before, during, or at the end of the chase, five versions of the Nabukelevu story state that one of the gods, either exhausted or fearful, hid under the sea from his rival.19 Then the pursuer, realizing where his quarry was hiding, drank the sea (or otherwise caused its withdrawal) to expose him. This anecdote may be a recollection of the precursor to a tsunami in which the ocean is withdrawn, typically to an unprecedented (memorable) distance/depth, prior to a giant wave forming and running ashore. It is interesting that there is no mention of this wave in any of the versions of the story collected, but we suggest that does not invalidate the link proposed between this detail and a tsunami; sometimes the withdrawal of water may be more memorable than the subsequent wave, especially if observers are high above the coastline, as they may have been on Kadavu at this time.

The place where the water withdrew is not certain, but Version 1B states that it was “below Tiliva [village] and above Nakasaleka”; the latter may refer to either the district or the village, some ten kilometers west of Tiliva. Two other versions (1B.1 and 1B.3) state the place as Nakasaleka, another (1B.5) as “near Nakasaleka.” It is proposed that Kavala Bay (shown on Figure 1B), an unusually large coastal indentation in which the withdrawal of water would

19 Some versions of the story state that Tautaumolau, the god of Nabukelevu, was the one who hid; other versions state it was Tanovo, the god of Ono. Rather like the issue of who was the pursuer and who was pursued, especially towards the end of the chase, we regard this as unimportant and likely to reflect storytellers’ allegiances rather than any original recollection.

79

consequently have been more noticeable than most other places along this part of the Kadavu coast, is the likeliest place for this story. This proposition is supported by the fact that Kavala Bay is centrally located within Nakasaleka District and adjoins the “hole made by the spear,” an incident that precedes the “hiding” in most Version 1 stories.

It should be noted that tsunamis are comparatively common in the Kadavu Islands owing to their proximity to a zone of lithospheric plate convergence and to the effects of earthquakes centered there (Rahiman and Pettinga 2006; Nunn and Omura 1999).

Age of Stories

Allowing for the probable inclusion of ancillary details about memorable events unrelated to volcanism, we consider that the thirteen stories recall a volcanic eruption of Nabukelevu. Within the three millennia that people have lived in the Fiji Islands, Nabukelevu has been active on at least three occasions (Cronin et al. 2004).

The earliest was that which formed the present summit dome, sometime before 560-380 BCE (2420 ± 90 BP).20 A subsequent event occurred sometime after 224-304 CE (1686 ± 40 BP) and involved landsliding and scoria deposition on the western side of the volcano around the village of Nabukelevuira. The most recent event occurred within the last 2,000 years, possibly as recently as 1630-80 CE, and involved flank collapse and the formation of a small dome on the northwest side of the volcano. There are details in some stories that allow us to favor one possibility over the others.

In Version 1A, the view of the sunset from Ono Island is more likely to have been blocked by a summit dome rather than a smaller flank dome, favoring the earliest of these three events. In the IB stories, the motivation of Tanovo to reduce the size of Nabukelevu is based on his jealousy about this mountain being higher than the one he occupied on Ono, again favoring the earliest volcanic event.

It is unlikely that the two most recent events would have produced an ash cloud of sufficient volume and extent to “drop soil” around Nabukelevu and farther away, a judgment that by default favors the earliest mountain-forming eruption as the source for the stories. The tsunami (inferred from the withdrawal of the sea) could have been caused by flank collapse of the kind that characterized each volcanic event at Nabukelevu, although the earliest would appear most probable because of its likely greater magnitude.

Finally, the fact that places far away from Nabukelevu, perhaps as far as Solo Island eighty kilometers distant (shown in Figure 5), are named in the stories as having been affected by Nabukelevu volcanism suggests that the memorable incident they recall was not localized, as appears to have been the case with the two more recent eruptive events. In support of this, several details in these stories, especially the throwing of the spear and the hiding beneath the sea, are likely to be located in Nakasaleka, fifty kilometers or so away, suggesting an event with more widespread effects is being recalled than that in the two most recent ones.

On balance we favor the summit-dome forming event dated to 800-350 BCE (or earlier)

20 Ages BCE are calendar years calculated from calibrated radiocarbon ages; BP (Before Present) dating refers to reported age in radiocarbon years, where “Present” is 1950 CE.

80

as the memorable event at the core of the Nabukelevu stories. Subsequent episodes of volcanism may have contributed to certain narratives, maybe even helping sustain their memorability and popularity among Kadavu people.

Discussion

This section discusses the nature of the volcanism stories from Kadavu, specifically the evolution of the relationship between such catastrophic geologic phenomena and the associated myths, before focusing in two subsections, firstly, on how such myths can function as social strategies for the preservation of collective memory and, secondly, on the use of such myths as risk-management strategies.

Geomythologists have attracted criticism for assuming there exists an etiological relationship between myth and geologic phenomena (Nordvig 2021). Yet there is no denying that myths of any kind which might explain/recall memorable geologic phenomena (like volcanic eruptions) are embedded in the worldviews of the people who observe them; for this reason, it has been argued that “disasters serve as social laboratories” (García-Acosta 2002:65), even revealers of the nature of ancient societies and the worldviews of their populations.

In this way, we can see that the stories about Nabukelevu volcanism naturally involve ancestral beings (vu in Fijian, often “gods” in translation) who can move through the sky and sea and air and are capable of superhuman feats (such as scooping out mountaintops and drinking the sea). Such beings were undoubtedly part of the worldview of Fijians 2,500 years ago which had evolved over previous generations, both within Fiji and beyond (Kumar et al. 2021; Burley 2013). For the earliest people had reached Fiji only about five hundred years earlier, their ancestors having developed their distinctive (Lapita) cultural identity in the Bismarck Archipelago (Papua New Guinea) a millennium earlier before setting out on intentional colonization voyages over the eastern horizon (Specht et al. 2014; Denham et al. 2012). No doubt their mythologizing of Nabukelevu volcanic eruptions was informed by the memories and understandings of their ancestors in the Bismarcks, who likely witnessed eruptions at Rabaul (Papua New Guinea), and perhaps at volcanoes in the Banks Islands (Vanuatu). Perhaps as they sailed east they also witnessed shallow underwater volcanism in Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, a phenomenon believed to explain the Maui (fishing-up of islands) myths across the Pacific (Nunn 2003).

But volcanic activity is comparatively infrequent in Fiji and adjoining island groups in the South Pacific compared to places like Iceland, Japan, and even Papua New Guinea where every generation is likely to experience (or hear about firsthand experiences of) volcanism. Consequently it is likely that the experience of catastrophic geologic events becomes more ingrained in the latter cultures than the former ones, where the multigenerational recurrence of volcanism (approximately every 500 years at Nabukelevu) means that it features more conspicuously in oral traditions. Anomalies require clearer explanation, as suggested by the place-specific, driver-specific nature of volcano myths in places like Australia (and of course Fiji), in contrast to places where volcanism (and kindred catastrophic phenomena) are far more frequent and consequently their understandings inform multifarious aspects of their mythologies.

81

Myths as Social Strategies for Preserving Memory

In preliterate societies, memories of catastrophic (or memorable) events often start to fade through time, their retelling in oral contexts becoming less believable. This may lead to a need to make such stories more compelling, something invariably satisfied by exaggeration and embellishment—their mythologization (Barber and Barber 2004). Yet we can infer, not least from the extraordinary longevity of many “myths” (Nunn 2018), that there remained in most such societies a strong desire to communicate a comprehensive (and expanding) body of information to each new generation to optimize their chances of survival. This was a particular imperative in uncommonly harsh environments, like arid Australia, earthquake-exposed Japan, and the drought-prone United States Southwest, for example. In this way, myths developed as “social strategies” for preserving memory, including the understanding of the natural environment and how and why it might change. Linked to this was an understanding about how its human occupants might confront and ultimately survive such change, a message with clear resonance for today (Nunn 2020).

In the case of Fiji and other pre-nineteenth-century Pacific Island societies, it is almost certain that knowledge about the island worlds in which they were situated was systematically passed on from one generation to the next, explaining why at the time of European contact in the late-eighteenth century, Pacific islanders were recognized as adroit sailors and navigators, for example (Irwin and Flay 2015; Lewis 1994). Stories about periodic catastrophe would have been an important component of this systematic knowledge transfer, not least because they were part of history, calibrating a people’s journey through history to the present, but also as part of future risk preparedness (Ballard et al. 2020; Galipaud 2002).

The Nabukelevu stories recounted above are likely to have been socially constructed as collective (or communicative) memories, principally to accommodate people’s observations and understandings of the uncommon volcanic phenomena they had witnessed. Yet while the earliest versions of these stories would inevitably have been situated within culture and worldview, they were not true cultural memories (Assmann and Czaplicka 1995). Only later, when the collective memories became sufficiently distanced in time did they morph gradually into cultural memories, sustained on Kadavu by the oral retelling of these stories and their linkages to place, such as the “footprint” and “spear-hole” shown in Figure 4, and even the anthropomorphization of landscape, as with the landscape of Ono Island and the body of Tanovo. Similar anthropomorphization occurs in Norse cultures (Nordvig 2021; Taggart 2018) and is interwoven with animist beliefs in many others in the Asia-Pacific region (Ballard 2020; Glaskin 2018).

In the same way as, for example, animist beliefs have become part of contemporary Buddhist practice in Cambodia (Work 2019), so it is clear that indigenous people in Fiji “often endorse simultaneous belief in distinct kinds of supernatural beings: the Christian God (Bible God) and various ancestor gods (Kalou-vu)” (McNamara et al. 2016:36). Such beliefs may help explain the longevity of Nabukelevu stories for probably more than two millennia, but it is also important to acknowledge the influence of language on this. All versions of the story collected from Kadavu for this study were rendered in one or more vernaculars that not only contextualized the narrative details but also secure their links to place in a way that might not have been possible if non-native languages had been used. This leads to the conclusion that

82

Nabukelevu stories represent mytho-linguistic constructions of environmental phenomena (Nordvig 2021; Barber and Barber 2004) and would likely fail to be sustained if either they could no longer be rendered in their original language or their mythical basis lost its credibility to become treated—as has been the fate of many “myths”—as worthless or at best entertainment (Deloria and Wildcat 2001; Vansina 1985).

Myths for Mitigation of Future Catastrophes

It seems clear that in most longstanding cultures located in places where catastrophic events periodically occur, an imperative evolved which entailed the systematic incorporation of every such event in oral tradition (as collective memory) in order for key details—what happened, how did it affect people, how did they cope—to be passed on to successive generations to optimize their chances of survival should a similar event affect them (Nordvig 2019; Lauer 2012; Sobel and Bettles 2000). The systematization of intergenerational pragmatic knowledge transfer may underlie our contemporary love of fiction; as Nunn put it, “our modern predilection for narrative may derive from our attention to survival stories” (2018:26).

Elements of “risk management” became part of cultural memory and thence what we today label as “religion” in ancient societies. This explains why religious beliefs are “so often tied to the experience of life-threatening situations and fear” (Nordvig 2021:22). In addition to functioning as both collective and cultural memories, the Nabukelevu stories—like many similar ones—also serve as part of a risk-management strategy, specifically to educate every new generation of Kadavu residents about the fundamental threat posed to their lives and livelihoods by this fractious volcano. There are many similarities to the Yuu Kuia (“Times of Darkness”) stories from the New Guinea highlands (Blong 1982) that are regarded by the Enga people as atome pii (“historical events”), not tindi pii (“myths”) (Mai 1981). Considering the Yuu Kuia, dense eruption clouds which blocked out the sun for several days, to have a supernatural cause, “people continued to live in fear, expecting that another event like the Yuu Kuia would bring . . . a worse disaster to them” (Mai 1981:127-28).21

A final point is that the mythologizing of catastrophe is not simply a trait of ancient or traditional societies. For example, contemporary myths around “climate change” and even the “coronavirus pandemic” abound, especially among people struggling to accept the profundity of associated threats or those who desire to reassure their constituencies that they remain in control (Wright and Nyberg 2014). Whether this realization means that constructions of myth in preliterate (oral) societies were not solely in the interests of group preservation is an interesting question that is beyond the scope of the present study.

21 The syncretism with Christianity, which arrived in the New Guinea highlands at least one hundred years after the Yuu Kuia, was articulated by an Enga informant around 1980 (Mai 1981:136): “I think the Yuu Kuia was caused by the power of God (Christianity). He shook the sky so hard that it caused the kati yuu (ash—the soil from the sky) to fall off.”

83

Conclusion

This study has presented and analyzed stories from the island of Kadavu in southern Fiji that plausibly recall a volcanic eruption which occurred in 800-350 BCE. These stories are well known among Kadavu people and others today, an example of the power of (largely) oral cultures to encode and preserve information about memorable events for thousands of years (Nunn 2018). Comparable stories about volcanic eruptions, commonly dismissed as myth or legend, found elsewhere also have an empirical basis that is in many cases helpful to reconstructing the precise sequence of component events. These include the pioneering work by Blong (1982) on “times of darkness” in highland Papua New Guinea, when it became shrouded with ash clouds; the research of Taylor (1995) into tephra eruption and deposition recalled by local stories in the islands of Tonga; and that of Cohen et al. (2017) on Gugu Badhun (Australian Aboriginal) stories about Kinrara (Queensland) eruptions around 7,000 years ago. Commonalities among stories concerning maar volcanism have also been analyzed recently (Nunn et al. 2019).

The existence of ancient stories about memorable events should encourage conventionally trained scientists to pay more attention to the traditional media through which these stories have been preserved and kept alive (Nunn 2018; Kelly 2015). There are practical reasons for this. In recent decades, it has been increasingly realized that the successful uptake of strategies for improving climate-change adaptation and disaster preparedness in rural Pacific Island contexts, for example, depends on an acknowledgement of traditional knowledge and practice (McMillen et al. 2017; Gaillard and Mercer 2013; Nunn 2009). Not only do these encourage ownership of such issues by the communities that drive them; they also ensure, as far as possible, that strategies are localized and informed by local residents’ collective memory of place.

Le Mans Université, France (Loredana Lancini and Rita Compatangelo-Soussignan)

University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia (Patrick Nunn and Taniela Bolea)

Fiji Museum, Fiji (Meli Nanuku and Kaliopate Tavola)

University of the South Pacific, Fiji (Paul Geraghty)

Acknowledgements

We thank Donald A. Swanson and an unnamed reviewer for their detailed and insightful reviews of an earlier version of this manuscript, which improved it greatly. We are also grateful to Sipiriano Nemani, Director of the Fiji Museum, for support. And especially to the people of Kadavu for their hospitality and generosity. Vinaka vakalevu kemudrau na turaga nomudrau wasea na nomudrau italanoa kei na nomudrau vakadonuya me wasei tale i vuravura.

84

References

Assmann and Czaplicka 1995

Jan Assmann and John Czaplicka. “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity.” New German Critique,65:125-33.

Ballard 2020

Chris Ballard. “The Lizard in the Volcano: Narratives of the Kuwae Eruption.” Contemporary Pacific, 32.1:98-123.

Ballard et al. 2020

Chris Ballard, Siobhan McDonnell, and Maëlle Calandra. “Confronting the Naturalness of Disaster in the Pacific.” Anthropological Forum, 30.1-2:1-14.

Barber and Barber 2004

Elizabeth Wayland Barber and Paul T. Barber. When They Severed Earth from Sky: How the Human Mind Shapes Myth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Beauclerc 1909

George A. F. W. Beauclerc. “Legend of the Elevation of Mount Washington, Kadavu.” Transactions of the Fiji Society, 22-24.

Blong 1982

Russell J. Blong. The Time of Darkness: Local Legends and Volcanic Reality in Papua New Guinea. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Burley 2013

David V. Burley. “Fijian Polygenesis and the Melanesian/Polynesian Divide.” Current Anthropology, 54.4:436-62.

Burley and Balenaivalu 2012

David V. Burley and Jone Balenaivalu. “Kadavu Archaeology: First Insights from a Preliminary Survey.” Domodomo, 25.1-2:13-36.

Cashman and Cronin 2008

Katharine V. Cashman and Shane J. Cronin. “Welcoming a Monster to the World: Myths, Oral Tradition, and Modern Societal Response to Volcanic Disasters.” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 176.3:407-18.

Clark and Anderson 2009

Geoffrey Clark and Atholl Anderson, eds. The Early Prehistory of Fiji. Terra Australis, 31. Canberra: Australian National University ePress.

Cohen et al. 2017

Benjamin E. Cohen, Darren F. Mark, Stewart Fallon, and P. Jon Stephenson. “Holocene-Neogene Volcanism in Northeastern Australia: Chronology and Eruption History.” Quaternary Geochronology, 39:79-91.

Cronin and Neall 2001

Shane J. Cronin and Vincent E. Neall. “Holocene Volcanic Geology, Volcanic Hazard, and Risk on Taveuni, Fiji.” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 44.3:417-37.

Cronin et al. 2004

Shane J. Cronin, Marie A. Ferland, and James P. Terry. “Nabukelevu Volcano

85

(Mt. Washington), Kadavu—A Source of Hitherto Unknown Volcanic Hazard in Fiji.” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 131.3-4:371-96.

Deane 1909

William Deane. “Tanovo—The God of Ono.” Transactions of the Fiji Society, 39-42.

Deloria and Wildcat 2001

Vine Deloria Jr. and Daniel R. Wildcat. Power and Place: Indian Education in America. Golden, CO: Fulcrum.

Denham et al. 2012

Tim Denham, Christopher Bronk Ramsey, and Jim Specht. “Dating the Appearance of Lapita Pottery in the Bismarck Archipelago and Its Dispersal to Remote Oceania.” Archaeology and Physical Anthropology in Oceania, 47.1:39-46.

Gaillard and Mercer 2013

J. C. Gaillard and Jessica Mercer. “From Knowledge to Action: Bridging Gaps in Disaster Risk Reduction.” Progress in Human Geography, 37.1:93-114.

Galipaud 2002

Jean-Christophe Galipaud. “Under the Volcano: Ni-Vanuatu and Their Environment.” In Natural Disasters and Cultural Change. Ed. By Robin Torrence and John Grattan. London: Routledge. pp. 162-71.

García-Acosta 2002

Virginia García-Acosta. “Historical Disaster Research.” In Catastrophe and Culture: The Anthropology of Disaster. Ed. By Susanna M. Hoffman and Anthony Oliver-Smith. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research. pp. 49-66.

Glaskin 2018

Katie Glaskin. “Environment, Ontology and Visual Perception: A Saltwater Case.” In Rethinking Relations and Animism. Ed. By Miguel Astor-Aguilera and Graham Harvey. London: Routledge. pp. 156-72.

Hames 1960

Inez Hames. Legends of Fiji and Rotuma. Auckland: Watterson and Roddick.

Hamilton and Mansfield 1971

J. Hamilton and N. Mansfield. Molau and Tanova. Suva: Fiji Education Department.

Henige 2009

David Henige. “Impossible to Disprove Yet Impossible to Believe: The Unforgiving Epistemology of Deep-Time Oral Tradition.” History in Africa, 36:127-234.

Irwin and Flay 2015

Geoffrey Irwin and Richard G. J. Flay. “Pacific Colonisation and Canoe Performance: Experiments in the Science of Sailing.” Journal of the Polynesian Society, 124.4:419-43.

Kelly 2015

Lynne Kelly. Knowledge and Power in Prehistoric Societies: Orality, Memory

86

and the Transmission of Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kumar et al. 2021

Roselyn Kumar, Patrick D. Nunn, and Elia Nakoro. “Identifying 3000-Year Old Human Interaction Spheres in Central Fiji through Lapita Ceramic Sand-Temper Analyses.” Geosciences, 11.6:238-48.

Lauer 2012

Matthew Lauer. “Oral Traditions or Situated Practices? Understanding How Indigenous Communities Respond to Environmental Disasters.” Human Organization, 71.2:176-87.

Lewis 1994

David Lewis. We, The Navigators: The Ancient Art of Landfinding in the Pacific. 2nd ed. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Mai 1981

Paul Mai. “The ‘Time of Darkness’ or Yuu Kuia.” In Oral Tradition in Melanesia. Ed. By Donald Denoon and Roderic Lacey. Port Moresby: University of Papua New Guinea. pp. 125-40.

Masse 2007

W. Bruce Masse. “The Archaeology and Anthropology of Quaternary Period Cosmic Impact.” In Comet/Asteroid Impacts and Human Society: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Ed. By Peter T. Bobrowsky and Hans Rickman. Berlin: Springer. pp. 25-70.

McMillen et al. 2017

Heather McMillen, Tamara Ticktin, and Hannah Kihalani Springer. “The Future Is behind Us: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Resilience over Time on Hawai‘i Island.” Regional Environmental Change, 17.2:579-92.

McNamara et al. 2016

Rita Anne McNamara, Ara Norenzayan, and Joseph Henrich. “Supernatural Punishment, In-Group Biases, and Material Insecurity: Experiments and Ethnography from Yasawa, Fiji.” Religion, Brain & Behavior, 6.1:34-55.

Nordvig 2019

Mathias Nordvig. “Katla the Volcanic Witch: A Medieval Icelandic Recipe for Survival.” In American/Medieval Goes North: Earth and Water in Transit. Ed. by Gillian R. Overing and Ulrike Wiethaus. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. pp. 67-86.

Nordvig 2021

______. Volcanoes in Old Norse Mythology: Myth and Environment in Early Iceland. Leeds: Arc Humanities.

Nunn 1998

Patrick D. Nunn. Pacific Island Landscapes: Landscape and Geological Development of Southwest Pacific Islands, Especially Fiji, Samoa and Tonga. Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific.

87

Nunn 1999

______. “Early Human Settlement and the Possibility of Contemporaneous Volcanism, Western Kadavu, Fiji.” Domodomo, 12:36-49.

Nunn 2003

______. “Fished Up or Thrown Down: The Geography of Pacific Island Origin Myths.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93.2:350-64.

Nunn 2009

______. “Responding to the Challenges of Climate Change in the Pacific Islands: Management and Technological Imperatives.” Climate Research, 40.2-3:211-31.

Nunn 2014

______. “Lashed by Sharks, Pelted by Demons, Drowned for Apostasy: The Value of Myths that Explain Geohazards in the Asia-Pacific Region.” Asian Geographer, 31.1:59-82.

Nunn 2018

______. The Edge of Memory: Ancient Stories, Oral Tradition and the Post-Glacial World. London: Bloomsbury Sigma.

Nunn 2020

______. “In Anticipation of Extirpation: How Ancient Peoples Rationalized and Responded to Postglacial Sea Level Rise.” Environmental Humanities, 12.1:113-31.

Nunn and Omura 1999

Patrick D. Nunn and Akio Omura. “Penultimate Interglacial Emerged Reef around Kadavu Island, Southwest Pacific: Implications for Late Quaternary Island-Arc Tectonics and Sea-Level History.” New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 42.2:219-27.

Nunn and Petchey 2013

Patrick D. Nunn and Fiona Petchey. “Bayesian Re-Evaluation of Lapita Settlement in Fiji: Radiocarbon Analysis of the Lapita Occupation at Bourewa and Nearby Sites on the Rove Peninsula, Viti Levu Island.” Journal of Pacific Archaeology, 4.2:21-34.

Nunn and Reid 2016

Patrick D. Nunn and Nicholas J. Reid. “Aboriginal Memories of Inundation of the Australian Coast Dating from More than 7000 Years Ago.” Australian Geographer, 47.1:11-47.

Nunn et al. 2004

Patrick D. Nunn, Roselyn Kumar, Sepeti Matararaba, Tomo Ishimura, Johnson Seeto, Sela Rayawa, Salote Kuruyawa, Alifereti Nasila, Bronwyn Oloni, Anupama Rati Ram, Petero Saunivalu, Preetika Singh, and Esther Tegu. “Early Lapita Settlement Site at Bourewa, Southwest Viti Levu Island, Fiji.” Archaeology in Oceania, 39.3:139-43.

Nunn et al. 2019

Patrick D. Nunn, Loredana Lancini, Leigh Franks, Rita Compatangelo-Soussignan, and Adrian McCallum. “Maar Stories: How Oral Traditions Aid

88

Understanding of Maar Volcanism and Associated Phenomena during Preliterate Times.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 109.5:1618-31.

Nunn et al. 2022

Patrick D. Nunn, Elia Nakoro, Roselyn Kumar, Meli Nanuku, and Mereoni Camailakeba. “How Island Peoples Adapt to Climate Change: Insights from Studies of Fiji’s Hillforts.” In Palaeolandscapes in Archaeology: Lessons for the Past and Future. Ed. by Mike T. Carson. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

Piccardi and Masse 2007

L. Piccardi and W. Bruce Masse, eds. Myth and Geology. London: Geological Society of London.

Poesch 1961

Jessie Poesch. Titian Ramsay Peale, 1799-1885, and His Journals of The Wilkes Expedition. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

Rahiman and Pettinga 2006

Tariq I. H. Rahiman and Jarg R. Pettinga. “The Offshore Morpho-Structure and Tsunami Sources of the Viti Levu Seismic Zone, Southeast Viti Levu, Fiji.” Marine Geology, 232.3–4:203-25.

Riede 2015

Felix Riede, ed. Past Vulnerability: Volcanic Eruptions and Human Vulnerability in Traditional Societies Past and Present. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Riesenfeld 1950

Alphonse Riesenfeld. The Megalithic Culture of Melanesia. Leiden: Brill.

Sobel and Bettles 2000

Elizabeth Sobel and Gordon Bettles. “Winter Hunger, Winter Myths: Subsistence Risk and Mythology among the Klamath and Modoc.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 19.3:276-316.

Specht et al. 2014

Jim Specht, Tim Denham, James Goff, and John Edward Terrell. “Deconstructing the Lapita Cultural Complex in the Bismarck Archipelago.” Journal of Archaeological Research, 22.2:89-140.

Steel 2016

Frances Steel. “‘Fiji Is Really the Honolulu of the Dominion’: Tourism, Empire, and New Zealand’s Pacific, ca. 1900-35.” In New Zealand’s Empire. Ed. By Katie Pickles and Katharine Coleborne. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 147-62.

Swanson 2008

Donald A. Swanson. “Hawaiian Oral Tradition Describes 400 Years of Volcanic Activity at Kīlauea.” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 176.3:427-31.

Taggart 2018

Declan Taggart. How Thor Lost His Thunder: The Changing Faces of an Old Norse God. Routledge Research in Medieval Studies, 14. London: Routledge.

89

Tavola and Tavola 2017

Kaliopate Tavola and Ema Tavola. The Legend of Tanovo and Tautaumolau. Ed. by Ruth Toumu’a. Nuku’alofa: Institute of Education, University of the South Pacific.

Taylor 1995

Paul W. Taylor. “Myths, Legends and Volcanic Activity: An Example from Northern Tonga.” Journal of the Polynesian Society, 104.3:323-46.

Tippett 1958

Alan R. Tippett. “The Nature and Social Function of Fijian War.” Transactions and Proceedings of the Fiji Society, 5:137-55.

Vansina 1985

Jan Vansina. Oral Tradition as History. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Veramu 1981

Joseph Veramu, ed. The Two Turtles and the Ungrateful Snake: A Collection of Myths and Legends. Suva, Fiji: Mana Publications.

Vitaliano 1973

Dorothy B. Vitaliano. Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Work 2019

Courtney Work. “Chthonic Sovereigns? ‘Neak Ta’ in a Cambodian Village.” Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 20.1:74-95.

Wright and Nyberg 2014

Christopher Wright and Daniel Nyberg. “Creative Self-Destruction: Corporate Responses to Climate Change as Political Myths.” Environmental Politics, 23.2:205-23.