Oral Tradition, 37 (2025):139-74

This song would be good if it were not so unnecessarily long.1 Although about 200 verse lines have been excised, this is the longest of all songs known to date. I could forgive him all the repetition and all the stretching out with nice language and diction, but I cannot forgive the transference of Bakony and the Danube in this song! The singer has also heard some Hungarian [Unđurski] songs and then transferred [those features] over from [those songs]. The transcriber would need to admonish him for this, then the singer himself would surely desist. This is what I reprimanded Hörmann for: the transcriber/collector must—as much as is possible—guide the singer to the correct telling, train him. I was not in Lepoglava, where the singer was imprisoned, so I could not do it; Mr. M. Križević is not an experienced collector.2

Dr. Luka Marjanović, June 18, 1889

This is one of many editorial notes written by Croatian lawyer and ethnographer Luka Marjanović on the archival manuscript3 containing songs collected from the Bosniak singer Ahmed Čaušević. The manuscript contains the transcriptions of eight long-format oral epic songs recited by the singer and transcribed by a law student named Mato Križević between January and early March of 1888. Like many song titles provided from folk singers, Čaušević’s songs carry simple titles denoting their protagonists. This song, number six in the collection, was called, A Song about Dizdarević Meho. Like many editors, Marjanović intended to alter the title to capture the action of the piece in a suitable literary aesthetic. Had it gone to press, the song was to be renamed, Dizdarević Meho Acquires a Bride for his Father, the Castellan of Udbina. The song, however, never saw publication, nor did any of the other seven.

1 I thank John Colarusso, Naomi McPherson, my anonymous reviewers, and the editors at Oral Tradition for their helpful comments. Thanks also to Radovan Marjanović Kavanagh for sharing an early manuscript of his great-grandfather’s memoir (Marjanović 2002); and to Klementina Batina for her ceaseless support in the archive. Some of this research derives from, or was collected during, fieldwork funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (File Numbers 767-2015-1599 and 756-2021-0001) and the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, which I thank for their generous support.

2 All translations are my own.

3 The manuscript is today housed in the archive at the Department of Ethnology of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (Hrvatska akademija znanosti i umjetnosti, hereafter HAZU) under call sign MH 122.

139

There are some parallels in the lives of Luka Marjanović (1844-1920) and Ahmed Čaušević (1863-?). Both were born in the frontier lands that divided the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires. As the crow flies, Marjanović’s hometown of Zavalje is only separated from Čaušević’s Brekovica by 12.6 kilometers; both villages are perched about 400 meters above sea level on mountains overlooking the city of Bihać. Phenomenologically, though, they were worlds apart. Brekovica was a midsized village, fully integrated into Ottoman Muslim society from shortly after its initial conquest in 1592. On the other hand, Zavalje had been formally established in 1795 as a Habsburg guard post on the Military Frontier (Vojna krajina) to defend territorial gains ceded to the Christian empire in the Treaty of Sistova (1791). Though Marjanović fondly remembered his family’s deep friendships with Muslim neighbors in Bosnia (2002:32, 52-54),4 the border zone had delineated strict military division of the two empires (53 n.17). Discontent over the shifted border had often led to cross-border raids led by local Muslim leaders to attack, plunder, and burn the defensive settlements on the Croatian side well into the first half of the nineteenth century (Dujmović 1999:66-67; Marjanović 2002:32). That same military border would be dismantled in the lifetimes of Marjanović and Čaušević as the Habsburgs took administrative control of Bosnia in 1878 and demilitarized and incorporated the border into the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia in 1881.

These dynamic, specific, and intimate local relationships would prove to be grist for the mill of the imperial and nationalist interests painted in broader strokes a short distance away in Croatian centers like Zagreb. Historically, much of Bosnia had once been medieval Croatian land (but also Bosnian and Serbian, among others). Centuries of war between the Habsburg and Ottoman empires had transformed the Slavic population in Bosnia into a foreign, Eastern Other for citizens of Croatia, even though historical memory, family histories, and linguistic connections carried the hope of reunification with ethnic kin and perceived co-nationals. When the Habsburgs took control of Bosnia, its territory and population became a matter of political and public interest in Croatia, Serbia, and Vienna. Imbued with the growing nationalist spirit of the times, Croatian politicians and intellectuals often treated Bosnia as their private “exotic East” (Jurić 2019a; Mažuranić 1842; Leskovar 1993) and sought to expand their spheres of cultural, intellectual, and territorial influence into the newly opened region by (re)connecting with what Edin Hajdarpašić calls their “(br)others”—simultaneously brothers and Others (2015:15-17).

Marjanović and Čaušević were two such (br)others. Both came from humble peasant roots and grew up in the Dinaric Alps surrounded by an active tradition of oral epic singing. At the age of nineteen, both left the frontier and came to the heartland of the Croatian nation where that art form brought them into contact. The resemblance of their stories, however, ceases there. For Marjanović, it was years of earnest study, sacrifices made by his family, support from his local diocese, and opportunities afforded to exceptional students in the Military Frontier that allowed him to leave Zavalje for Otočac (1857), Senj (1858), Zagreb (1863), and finally Vienna (1869) to further his education (Marjanović 2002:56-86). In the latter two cities, Marjanović pursued a career in law and education, becoming a respected scholar, professor, socialite, and political actor in Zagreb. In contrast, the illiterate, peasant farmer Čaušević was removed from

4 In this article, page-number citations follow a colon after dates, while song numbers follow a period (for example, Hadžiomerspahić 1909.1)

140

Brekovica at the age of eighteen by imperial gendarmes for an unknown crime, tried in Sarajevo, and transported to the prison in the northern Croatian town of Lepoglava. It was a highly unique folklore collection project, conceived and executed by Marjanović and including Čaušević, that brought these two together. Unfortunately, their dissimilar social backgrounds also reflected an aesthetic divide between an oral singer working within a system of traditional folk practice and a scholar who, despite his best intentions, approached the songs from a high-cultural and rationalistic position. As my introductory quote attests, Marjanović found a number of problems with Čaušević’s songs. What is curious in the passage, though, is that stylistic concerns are superseded by those of a geographic nature. Why was the transposition of a mountain and a river cause for such a rebuke?

At the heart of this problem is an asymmetry of imperatives rooted in the highly divergent educations and social standings of two individuals—the gentleman scholar and the peasant singer—working from disparate expectations. In this article, I outline the notable folklore project that brought Marjanović and Čaušević together; the cultural divide that engendered a disconnect between the two; and the important role that the mountain Bakonja, the epic version of Bakony Mountain in Hungary, played in that conflict. I question Marjanović’s decision to replace Bakonja with another mountain in Čaušević’s songs, bringing to this problem the benefit of temporal distance and a legacy of artist- and tradition-centered research that has developed since Marjanović’s time. I seek to understand this clash of cultures and pose the question that Marjanović was too disparaging to ask: why did the tradition allow for this presumed error? To this end, I combine historical archival research with contemporary geographic fieldwork, returning to Marjanović’s surprisingly neglected collection project and to the topic of epic geography to support Daniel Prior’s position that place names and itineraries “warrant nomination . . . to a status near that of epithets and other formulae in the set of comparative tools available” to epic scholars (1998:272). By returning Čaušević’s Bakonja to the Lika region of Croatia where he situated it, we can better understand the conceptual geographies adopted and employed by epic singers and why they sometimes clashed with the editor’s imperative. Reflections on this case reveal why Marjanović’s dedication to a rationalist’s standard precluded him from the important conclusions of his immediate intellectual successors, Matija Murko and Milman Parry.5

Marjanović and the Muslim Singers

In 1863, during the summer vacation that would bridge his pedagogical transition from Senj to Zagreb, Marjanović made a first pilgrimage to the capital before returning home. Settled in his family home, the eighteen-year-old treated his kin to a reading of the literary-epic songs of Andrija Kačić-Miošić; they surprised him by countering that they too knew such songs. Taking to heart the advice of his teacher, the philologist and literary historian Franjo Petračić, who encouraged students to record folklore while home over the summer break, he proceeded to

5 On the empirical and theoretical advances of Marjanović, Murko, Parry, and Lord, see Buturović 1992:105-48, 162-262, 556-76.

141

collect songs from his family and neighbors (Marjanović 2002:81-82). He showed them to his new teacher in Zagreb, the renowned Slavicist Vatroslav Jagić, who recognized their quality and helped Marjanović, then just twenty years old, to bring them into print. His book, Croatian Folk Songs Sung in the Upper Croatian Frontier and in Turkish Croatia (1864), contained twenty-seven epic and fifty-five lyric songs and would later prove to be Marjanović’s ticket into Zagreb’s academic community. After completing his Ph.D. in Vienna in 1872, Marjanović returned to Zagreb to teach canon law as professor, and later dean, of the Faculty of Law at the University of Zagreb. It was there that he became embroiled in the mass folklore collection project begun by the publishing house and cultural institution Matica hrvatska (hereafter “Matica”).

Starting with a public call in 1877, Matica’s administrative board began the compilation of a series of volumes of Croatian epic songs. Calls for materials were answered by a range of collectors throughout Croatia and Bosnia, including Marjanović, who had continued to gather songs in his home region in 1866, 1867, and 1869. He offered his extended manuscript to Matica in 1877, and the board returned a highly positive assessment in 1886, effectively bringing him into the fold of the institution and its larger collection project. With work moving forward on the first two volumes (HNP I and II, published in 1896 and 1897, respectively), Marjanović and Matica’s secretary-treasurer, Ivan Kostrenčić, argued that one voice lacking from the collection was that of their “brothers of the Mohammedan faith” (Uprava 1887:24) in “Turkish Croatia” (see Mesić 2001:11 n.11): that is, the northwestern tip of Bosnia, also known as the Bosnian Frontier (Bosanska Krajina, hereafter “Krajina”).6

The two scholars proposed to bring that voice to the Croatian reading public and, in the spring of 1886, Marjanović enlisted his oath-brother (pobratim),7 the merchant Jozo Ivković from the city of Bihać, to track down Muslim singers. In July of that year, Ivković’s trade brought him to Zagreb, and he carried with him a present for Marjanović: a song he had transcribed from the singer Mehmed Kolak Kolaković, a “pure-blood Mohammedan” (Muhamedanca čiste krvi) from the town of Orašac (Marjanović 1898:vii; Matica hrvatska 1877-89, document 102, p. 1). With a contact made and news of the project spreading in the Krajina, Marjanović recruited friends, students, and colleagues as transcribers and embarked on

6 It is notable that, as a native of the Krajina, Marjanović had to learn this nationalist rhetoric in the capital. In the preface to his 1864 collection, he reveals being conflicted about applying the Croatian name to the book, relating that peasants on both sides of the frontier were unfamiliar with the Croatian and Serbian ethnonyms. Krajina natives referred to themselves as Bosniaks (Bošnjaci) if they were Muslim and as Hungarians (Madžari) if they were Christian (Marjanović 1864:vi; see further Jurić 2019a:21 and 2020a:14-17). By 1887, these nuanced and emic ethnographic observations had been abandoned in favor of nationalistic interests. In 1888, Marjanović firmly rebuked Kosta Hörmann for not choosing the Croatian or Serbian ethnonym for his collection, saying it further divided their nations and confused foreign readers (Marjanović 1888b:488-89). For more on the 1864 preface, see Tate 2011.

7 Among a range of other fictive kinships, traditional Western Balkan society included the practice of oath-brotherhood (pobratimstvo) and oath-sisterhood (posestrimstvo). This is akin to the English-language concept of blood-brotherhood and was sometimes sanctified with an exchange of plasma; however, one could also institute the connection simply by invoking another as a brother or sister. This most often applies to martial contexts where friends, and even enemies, accept each other as brothers or sisters, sometimes drastically altering their social and martial relationships. It could also be used to alter the course of social interactions: for example, a maiden who does not wish to marry a suitor invoking him as a brother to save herself from the union. The practice features heavily in epic songs. For a detailed treatment, see Bracewell 2016.

142

the first truly scientific program for epic song collection in the Western Balkans. Marjanović assembled a team, consisting of an informal and shifting roster of fifteen individuals working in various capacities at different times, but predominantly composed of Marjanović and his trusted assistant, the lawyer Petar Starčević (see Mučibabić 1982). Between September 16, 1886, and late November, 1888, they made five trips to the Krajina, brought three singers to Zagreb for extended stays of song collection and public performances, and received a number of other songs sent in by various collectors. In total, the team amassed 290 epic songs and thirty lyric songs from only thirteen singers, with the epics amounting to a total of 255,388 verse lines (Jurić 2023a). Fifty of these songs were published in full in the two Croatian Folk Song volumes that Marjanović edited for Matica,as well as portions or descriptions of sixty-eight other songs in the books’ appendices.8

Marjanović was rigorous and exacting in his collection work and provided a wealth of data in the first volume’s introduction. He gave biographies for the singers and described their singing styles and techniques as well as their artistic influences, tracing the trajectory of the tradition in brief. He included high-quality photographs of four of the singers and even relayed minor details about the project, such as the remuneration that singers received. Collecting a broad range of songs from a number of singers (including the complete repertoires of two) drawn from a single geographic region provided Marjanović rare insight into the craft. He was one of the first scholars to offer systematic observations about song performance and to note that the texts of the songs were not fixed but frequently changed between performances, even by the same singers (1888a:478 and 1898:xxxi). These observations, gleaned unintentionally from empirical circumstances, had a foundational influence on the later studies of scholars like Matija Murko and Milman Parry who were able to test a series of increasingly complex hypotheses about the functioning of the art form in the age of sound recording technology. From his earliest collection work, Marjanović also noted the tendency of Krajina singers to pepper their decasyllabic songs with eleven- and twelve-syllable lines: not in error, but as an intrinsic aspect of the singing in the region (1898:liv-lv). A scrupulous proponent of the epic art, Marjanović defied the standard editorial practices of his forebears and faithfully reproduced many of these hypersyllabic lines in publication. His work was heralded at the time for its academic rigor and careful attention to conveying the true art of the singers. It was quite a shock, then, to later scholars reviewing Marjanović’s manuscripts, to see the extreme level of redaction and rewriting he had applied to the songs he had published (Buturović 1992:571-74; Krstić 1956; Mučibabić 1981; Lord 1991:35-36, 108, 125, and 1995:16-18, 223).

Like the great collectors before him, Marjanović still followed an editorial prescription to refine the roughhewn songs of peasant artists in service of literary tastes. He did not follow Vuk Stefanović Karadžić in taming all hypersyllabic lines and removing profanities (see Foley 1995:70), but his editorial tactics exceeded Vuk’s in other ways. Despite some of his own contrary claims (1864:ii and 1888b:488, 491-92), Marjanović rearranged sung lines if the flow of the narrative seemed erratic and readily dissected and recombined neighboring verses if he felt the corrections fostered a brisk narrative pace. Conversely, he expanded terse lines, filling in

8 Matica promised funds for a third volume in 1890 but this never materialized (Marjanović 2002:223). It is possible that some of Čaušević’s songs were slated for publication in that volume.

143

narrative context from his own pen, and often corrected language and syntax. He also abhorred two of the central operating mechanisms of epic singing—repetition and parallelism—regularly excising large blocks of verse, even full pages, in which characters related occurrences that had already been described. And these only represent the alterations applied to the final collected songs on paper. Marjanović was clear in many of his writings about the role that a collector must serve in training singers how to dictate their songs “correctly” and the need to alter the course of a performance when a singer errs (Marjanović 1888a:478, 1888b:488, 490, and 1898:xxiii, xxxviii). Albert Lord would later write of Marjanović’s edited manuscripts: “I have not seen any better proof of the existence of two poetics, one for oral-traditional poetry and the other for written literary poetry” (1991:125).

All these stylistic “problems” were the primary focus of Marjanović’s scathing and extended critique of the collection of Bosniak epics published by Austria-Hungary’s Bosnian representative for cultural affairs in Sarajevo, Konstantin (Kosta) Hörmann. In May of 1887, when Marjanović’s collecting project was in full swing, rumors reached him and Matica’s board that a competing project had begun in occupied Bosnia. Backed, though not initially guided, by the imperial state, Hörmann had employed a wide range of assistants coordinated by Bosniak intellectuals to collect epic songs across the entire territory of Bosnia-Herzegovina (Buturović 1976:12-42; Bynum 1993:587-88, 600-01). As Marjanović understood the case, Hörmann had started his collecting soon after Matica first announced its project to Croatian news media. When he learned that Hörmann’s men had been courting his star singer, Kolaković, the race became personal (Matica hrvatska 1877-89, document 105, p. 3; cf. Buturović 1992:568). Hörmann (1889:iv) later denied that his project was instigated as an effort to forestall Matica’s, contending that he had started collecting in 1880 (611) and that, out of respect for Marjanović, he had avoided the Krajina when he learned of Matica’s project (iv). However, he also denied that the publication of the first volume in 1888 had been rushed to preempt Matica’s (iv), which has proven untrue (Buturović 1976:18).9 The stakes were not only academic but also political; the imperial state had vested interests in producing publications that celebrated Bosniak Muslims as their own unique national entity, removed from Greater-Croatian and Greater-Serbian irredentist aspirations (Hajdarpašić 2015:176-86; Marjanović 1888b:488-89).

Marjanović read in Hörmann’s highly uneven and often minimal editorial interventions an intellectual attack on his work at the service of political machinations. Between July 28 and August 15, 1888, he published a critical, twenty-page review of Hörmann’s first volume over several issues of the journal Vienac (Marjanović 1888a-h; for summary and analysis, see Buturović 1976:66-68). In it, he chastised the poor and uneven quality of the songs, suggesting this was due in large part to a lack of training and vetting of Hörmann’s collectors, as well as to a hands-off editing approach. He made sure, rather petulantly, to remark upon the rushed form of the final product; to assert the role that his own collection played in that haste; and to use the opportunity to promote his upcoming publication.

Now beaten to the punch, Marjanović’s disappointment was mitigated by the relaxed pressure for timely publication. Instead, he refocused his efforts towards ensuring that his

9 Buturović (1976:18-21) largely accepts Hörmann’s account in his rebuttal, though, when she reviewed the controversy, she seems to have been unaware of the archival document referenced above (Matica hrvatska 1877-89, document 105), which notes that Kolaković had been propositioned by one of Hörmann’s collectors.

144

collection would overshadow through quality any value Hörmann’s held through anteriority. He spent the next few years preparing his two volumes for publication, rewriting tens of thousands of manuscript lines written hastily in the field in clean form on long-format quires. To these transcripts, he applied veritable mountains of ink, writing, rewriting, moving, correcting, and leaving short and extended comments in the margins directed at himself, other members of the editing team, and the printers. And yet, the majority of Marjanović’s concerns were stylistic. He was steadfast in producing a concise and unencumbered narrative and felt at liberty to intervene freely on those grounds. On the other hand, he seldom applied corrections to song content and then always most subtly and judiciously, with the aim of interfering in the world of the epics as little as possible. It is thus surprising that the one issue that vexed him most in Čaušević’s songs was geography.

Ahmed Čaušević and His Epics

In 1887, the young teacher Dragutin Hirc—not yet the esteemed botanist, mountaineer, and academic he would later become—took a job at the state penitentiary in the northern Croatian town of Lepoglava, providing a foundational education to the inmates. Newspaper reports describing Matica’s project and Mehmed Kolaković’s visit to Zagreb prompted Hirc to enquire among the Bosnian inmates in search of another “Kolak.” One of his students informed him of a young epic singer, Ahmed Čaušević Behlilović,10 who was tasked with chopping firewood for the prison. Hirc sent pen and paper to the singer along with a request for his songs. Čaušević, who had only learned to write since his incarceration, used these to reply that, though he knew many songs, he was not up to the task of committing them to paper. Unable to dedicate the time required to record them himself, Hirc delegated this task to a young law student (pravnik), Mato Križević, who was working as a private tutor (informator) to the sons of the prison’s director, Franjo Tuđaj (Hirc 1888:3; Marjanović 1898:xxxii). Križević contacted Marjanović and sent him the titles and first two dozen lines of thirteen of Čaušević’s songs, only two of which were variants of songs collected from Kolaković (Hirc 1888:3; Križević 1888a and 1888e). The quality and novelty of the songs revealed a worthy singer, and on January 20, 1888, Matica’s executive board allocated funds to Križević and Čaušević to begin transcription.11 On Matica’s suggestion, the prison director moved Čaušević into the prison’s kitchen and gave him

10 This third name is puzzling. Hirc (1888:3-4) presents it like a compound surname. The Zenica prison index (KPZ 1886-1939) records it in a slightly altered form, Behligović, and as a nickname. Muslim men (and sometimes women) in the Krajina commonly carry sobriquets, but they tend to be shorter and not to mirror patronymics. Notably, two other Čauševićes listed in the KPZ record carry a nearly identical nickname, Behtigović, suggesting some relationship between the names.

11 Križević was paid 100 forints for the task (Matica hrvatska 1877-89, document 118, p. 3). That sum included an advance of 25 f. in retainment and to purchase supplies. Čaušević received a total of 10 f. on February 23 for his singing, a common sum given to singers with smaller repertoires who were not brought to Zagreb (116:1). One can compare his remuneration with that of Kolaković, who was given 130 f. and various gifts in Zagreb (Marjanović 1898:xvii-xviii) and whose primary collection cost Matica about 370 f. (Matica hrvatska 1877-89, document 105, p. 3; 116:1; Tuđaj 1888:1).

145

lighter duties, freeing him up from five to ten o’ clock each evening to dictate his songs in the prison school (Hirc 1888:3).

Čaušević was born in 1863 in the village of Brekovica just northeast of Bihać. At the age of fourteen, the singer began to learn heroic songs, first from his father and his older brother, Alija, and later from two brothers-in-law: Hasan Majetić, a native of Ostrožac; and Ahmo Samarđić of Mutnik, who married his sister Hanka (Hirc 1888:3-4; Križević 1888a:2; Marjanović 1898:xxxii). Čaušević quickly gained proficiency in the art of singing to the two-stringed tambura: a simple, likely Central Asian-derived, lute-like chordophone that characteristically accompanied epic singing in the region (Talam 2009). He spent his workdays farming his family land with his older brothers Alija and Omer; but, in his spare time, he traversed the territory between Bihać and Cazin, singing epics and learning from other singers.

In the summer of 1881, Čaušević’s parochial circumstances were irrevocably altered when he committed a “grievous crime” (teški zločin), leading to his incarceration. He stood trial in Sarajevo, receiving a sentence of ten years on September 21, 1881.12 Since there were no closed-type prisons in the newly occupied Bosnia, Austrian authorities transported Čaušević to Lepoglava on November 16, 1883 (or rather, as I believe, 1882), to serve his sentence.13 In 1886, with the opening of the Kazneno popravni zavod Zenica (“Zenica Penal Correctional Institution,” hereafter KPZ), the process was initiated to transfer Čaušević, along with his fellow Bosnian inmates, closer to his home region to finish his sentence. In 1888, with this transfer date looming, there was a rush for Križević to collect as much material from Čaušević as he could. Funds from Matica and appeals to the prison director freed Križević and Čaušević from their duties (Križević 1888a:3, 1888b:3, and 1888c:3; Tuđaj 1888); and eight long-format epics14 were recorded before Čaušević was transferred, somewhere around March 10, 1888 (Križević 1888c:3). As prisoner number 45, Čaušević finished the last three years of his sentence at KPZ and was released on September 21, 1891, at which time he disappears from the historical gaze (KPZ 1886-1939). The mosque in Brekovica retains no marriage, birth, or death certificates from this era; I have been unable to find a grave marker in the oldest graveyards in his village, and no memory of him remains in the oral histories of the contemporary families in the town who share his surname.

12 All mention of Čaušević’s felony is shrouded in euphemism: “grievous crime,” “unfortunate event,” “greed of gain” (pohlepa za dobitkom) (Hirc 1888:4). No sentences are noted in the KPZ register, only an opaque note, “V.r. 2406/I,” which may represent a codified sentence (current prison staff have not yet responded to requests for clarification). Lepoglava’s register (Lepoglava 1883-97) begins in 1891, after Čaušević’s transfer, but includes prisoners from his time and their sentences. Rapes generally garnered three to five years, while thefts averaged two to five (the longest sentence is twelve). Sentences for murder run from three years to life imprisonment, although the average was fifteen years. From the available data, I speculate that Čaušević’s crime was manslaughter with theft as a possible motive; his age might have been a mitigating factor in his sentencing.

13 Hirc (1888:3) gives 1883, having incorrectly recorded the year of Čaušević’s conviction as 1882. I am convinced his dating of Čaušević’s transfer to Lepoglava carries forward this error. Hirc made several such mistakes about Čaušević, including incorrectly noting his hometown as Orašac in a later autobiography (Cuvaj 1913:379).

14 The songs are: (1) The Song of Serdar Maleta; (2) The Song of Lipovača Meho; (3) Mujo Hrnjica and Husein Babić; (4) The Song of Meho Dizdarević; (5) The Song of Two Maidens; (6) The Song About Meho Dizdarević n. II; (7) The Song of Osman Čustović; and (8) Delalija Bojčić. See Jurić 2023a for all of Marjanović’s titles and song lengths. In this article, I follow Čaušević 1888 for song numbers and names but cite verse lines in the unedited forms. These are easier to follow in Križević 1887/1888.

146

Hirc describes the singer at twenty-five as having a “pleasant appearance, brown-skinned, with small black mustaches and bright black eyes” (1888:3). Despite Čaušević’s scandalous position in society, Križević described him in positive moral tones, painting a picture of a gentle soul who had been the victim of an unfortunate event (nesretni slučaj). Marjanović readily capitalized on this depiction, which connected the singer to common stereotypes of pious but dangerous epic heroes (both medieval knights and hajduk bandits), while also making concessions to condone the inclusion of an unsavory character in the song project. To this effect, Marjanović echoed Križević’s words in his published description of Čaušević: “As the prison warden himself attests, that youth is one of the most upstanding convicts. Sincerity, a soft heart, and an honest soul are revealed in each and every one of his words, and it can truly be said that only an unfortunate incident has driven him to this hapless position” (Marjanović 1898:xxxii; cf. Križević 1888a:2).

What truly distinguished Čaušević, though, was his songs. Križević conveyed the singer’s personal boasts about his excellent memory for new materials and his considerable performance experience. He claimed that, while a free man, “he had sung every song known to him 50-100 times and had little trouble learning them. ‘As soon as I hear a song once,’ he says, ‘I can sing it thus word for word’” (Križević 1888a:2). Impressed with their singer but also trying to sell their intangible cultural product to Marjanović and a wider audience,15 Hirc and Križević stressed that six years of imprisonment had not impaired Čaušević’s ability and that he occasionally sang for his friends in prison (Hirc 1888:3; Križević 1888a:2). The distinguishing characteristic of his singing was the considerable length of his songs. Križević collected eight songs from the singer totaling 23,195 verse lines (average length: 2,899 lines), with three songs exceeding 4,000 lines and the longest comprising 4,447—by far the longest epic song collected in the Western Balkans before Milman Parry’s fieldwork. Čaušević also learned a few of his songs from two of Marjanović’s other singers, Omer Ukić (or Hukić) and Hasan Majetić. In the case of Majetić, this gave Marjanović the opportunity to compare a student’s songs to his teacher’s, a thitherto unexplored line of inquiry (Marjanović 1898:xxxiii). Čaušević’s versions were greatly expanded with his longest song almost three times the length of his teacher’s version (Majetić at 1,547 lines vs. Čaušević at 4,447).

With the benefit of a contemporary perspective, informed by a strong understanding of the breadth and shape of the Bosniak epic tradition and by the insights of the oral-formulaic school, Čaušević’s songs can best be described as the product of a highly gifted but still unrefined epic singer. His singing often exhibits faults—in a sense that is emic to the tradition—that reveal his age. In 1888, he was a young singer who had not yet mastered the art. He misuses some stock phrases and formulae (though perhaps in an intentional attempt at novelty), and relies heavily on hendecasyllabic lines (although this might be a product of the slow pace of dictation

15 Križević, like other collectors of the time (Jurić 2020b:34), was eager to expand his opportunities with the esteemed Zagreb academics now that he had their attention. While he was collecting Čaušević’s songs, he compiled a list of notable Bosnian singers from the inmates. He then offered to collect from three other inmate-singers and to make an excursion to Bosnia at Matica’s behest (Križević 1888b:1-3). Kostrenčić seems to have extended an offer to Križević to travel to Bosnia with them, but he was forced to decline due to obligations at the prison (1888b:3). A subsequent offer of some unknown job was met with opportunistic bargaining and leveraging for higher pay, which seems to have precluded further discussion (1888d:2).

147

to a collector writing by hand).16 He regularly employs standard formulaic language and is prone to reusing mundane lines with little variation and to extending repetitive episodes. That said, his ability to perform extremely long songs is a testament to an artist who was learning to flesh out his stories and give their plots sufficient time to breathe and captivate their audience. While the length of his songs largely stems from simple elaboration, many boast long sections of competent and dynamic singing, including many short passages graced with dramatic touches and surprising flourishes of poetic genius that are unique to his telling. These have the effect of bringing an air of realism to scenes, inserting flashes of unexpected humor, or captivating the listener with remarkably descriptive and detailed vignettes full of subtle and insightful flashes of recognizably human behavior. In Čaušević, I see a singer who might have rivaled Milman Parry’s prized Avdo Međedović had his songs been recorded at age fifty rather than twenty-five. The notable aspects of his singing and its collection which concern us here, though, are twofold. Firstly, his songs were not collected by Marjanović’s team. As a result, he was not coached to sing the songs “properly,” and thus Marjanović’s intervention was limited to editing the largely accurate transcription of his dictated verse. Secondly, Čaušević had an odd tendency to pluck Bakonja mountain from out of Hungary and move it to the border between the Croatian regions of Lika and Ravni Kotari.17

While Marjanović was impressed by the length of Čaušević’s songs and noted that many passages were well sung, this exceptional length was produced through the use of stylistic methods—namely, parallelism, repetition, and elaboration—that offended Marjanović’s sensibilities. The exceptional length of his finest songs also posed practical impediments for inclusion in two already oversized volumes of published epics. Marjanović conducted extensive revisions and edits on the transcriptions of Čaušević’s songs, hoping to publish at least one of them. In the end, page-length constraints and the fact that other singers had performed competent versions of the same songs meant that Čaušević’s work was relegated to the archive, only occasionally mentioned in the appendices to note multiformity. What is somewhat surprising, though, is the amount of ink Marjanović spilled railing against Čaušević’s tendency to insert Bakonja into the Lika. Of all the singer’s presumed faults, none galled the editor more than this. A closer examination of this habit has much to teach, not only about epic geography and Čaušević’s singing style but also about the editor’s imperative and how these clashed in this seemingly insignificant collaboration.

16 Križević wanted to furnish Čaušević with a two-stringed tambura in hopes of getting a “fuller” song (it is unclear where he planned to obtain the instrument), but Čaušević assured him that he could sing competently bare-voiced (gologlasno) and that the prison was not a suitable place for accompanied singing (Križević 1888a:2). Parry and Lord definitively showed that recitation negatively affected song form for bards trained to sing with accompaniment (Lord 2019:133-37). However, Marjanović notably contended that singers insert more hendecasyllabic lines when singing to the tambura (1898:liv).

17 Marjanović also notes transference of the Danube (Dunav) river in the quote above. I have not pursued it here, because it occurs in only one song (song 6), and it is not clear that the river has actually been moved. In a stock motif within the song, the Castellan (dizdar) of Udbina offers to give a series of gifts to any hero willing to travel to Zadar and free his imprisoned son. Beyond conventional rewards, he includes a ferryboat he owns on the Danube, which is a source of great income (Čaušević 1888.6, ll.2229, 2509, 2615, 4437; see also HNP IV.48). Though it is a stretch for the Castellan to own a ferry in northern Hungary, Čaušević remains exonerated, having never given a location.

148

Mountains in the Epic Tradition

The traditional epics of Western Balkan singers can generally be classed into three temporal cycles: (1) songs concerned with medieval heroes and events; (2) songs covering the premodern period of imperial warfare and constant cross-border reaving on the Triplex Confinium; and (3) later songs concerned with wars and political events in the era of nation-states. The vast majority of Bosniak epics were concerned with the second category given that it covers a span of history when Ottoman culture was at its apex and its territorial incursion into Europe at its greatest. Within this cycle, Krajina epics are usually divided into two emic categories focused on the wars, weddings, and razzias of Christian and Muslim heroes and villains. The most abundant are the Krajina or Lika Songs (krajiške/krajinske/ličke pjesme) regarding the border that separated the Ottoman-controlled Sanjak of Krka and Lika (BCMS Krčko-Lički Sandžak, Turkish Kırka sancağı, held 1580-1688) from the Venetian-controlled territory of Ravni Kotari in Dalmatia, with the city of Zadar as its center. The lesser category is the Hungarian Songs (unđurske/ungarske pjesme) which concern battles between Ottoman-controlled Hungary (1541-1699) (with Buda, Osijek, and Kaniža18 as the major centers) against the Austrians in Vienna and their satellite principalities.

Since the heroes of these songs often traverse great distances (to raid and plunder; to carry off slaves or kidnapped maidens; to retrieve women who have been betrothed to them; to conduct sieges and warfare), epic geography played an important role in orienting listeners to unfolding events. Settings are generally focused on commonly known cities; the defiles where ambushes are set; the springs and wells where characters meet; and the fields where battles and duels are conducted. In shorter songs, or those of less skilled singers, the geography beyond the cities is often very minimal and regularly fictional. These geographic features are sometimes named for known locations, but the vast majority are adumbrated in stock traditional style. Fields are named after the cities they surround (Udbinjsko polje, “Udbina field”) or else given generic names common to multiple areas (kamensko polje, “rocky field”; vedro polje/vedrine ravne, “clear field”/“clear flats”; and so on). The defiles are named for the mountains they bisect (bakonski klanac, “Bakonja defile”) or the towns they lead to (as in, Ripački klanac, which leads to the town of Ripač), or are given symbolic names like Jadikovac (“Lament,” due to the ambushes and deaths that occur there). In the simplest songs, mountains that are crossed are often left unnamed or else drawn from a limited, common list, though a more extensive catalog was employed by skilled singers (Marjanović 1898:liii).

In the highly elaborated and extended songs of accomplished singers, epic geography took on a heightened level of accuracy. Here directions of travel between two points are given specific itineraries which mark both real and imagined topographic features, with some singers deploying elaborate geographies with multiple routes between major points. These oral itineraries appear to be adopted regionally and through inheritance and were likely cultivated in the same manner as the art of singing. The data available in the HAZU collection for song

18 Nagykanisza, possibly blended with Kanjiža in Vojvodina in the folk imagination/history.

149

transmission between singers is too little to permit a thorough investigation of when and how singers adopt epic itineraries, though the examples available suggest a predictable system. Singers likely learned some fundamental itineraries in their youth. Then, depending on various aspects of their character, personal travels, contact with other singers, and artistic skill, they proceeded to refine or alter this fundamental stock to varying degrees as they encountered other singers with firsthand experience of locations—those already in the neophyte’s songs and, especially, in newly adopted songs with theretofore unsung locations.19 Given that many peasant singers lived largely regionally-bounded lives and were most often minimally educated or uneducated altogether, it is understandable that proximate geography was rendered more accurately than more distant locations. Refined mental mapping seems to have been largely based on firsthand travel experience, though one cannot rule out careful cultivation and judicious vetting of song adoption from other singers. Mehmed Kolaković, for example, belongs to a rarer rank of bards with accurate geographies in far-flung locations. His songs set in southern Bosnia-Herzegovina present accurate or near-accurate ordering of cities, towns, and geographic features, and even relatively convincing estimates of distance. Some of this can be ascribed to his personal travel history (Marjanović 1898:xii), but careful cultivation of heard song content and perhaps historical narrative must play a role as well.20

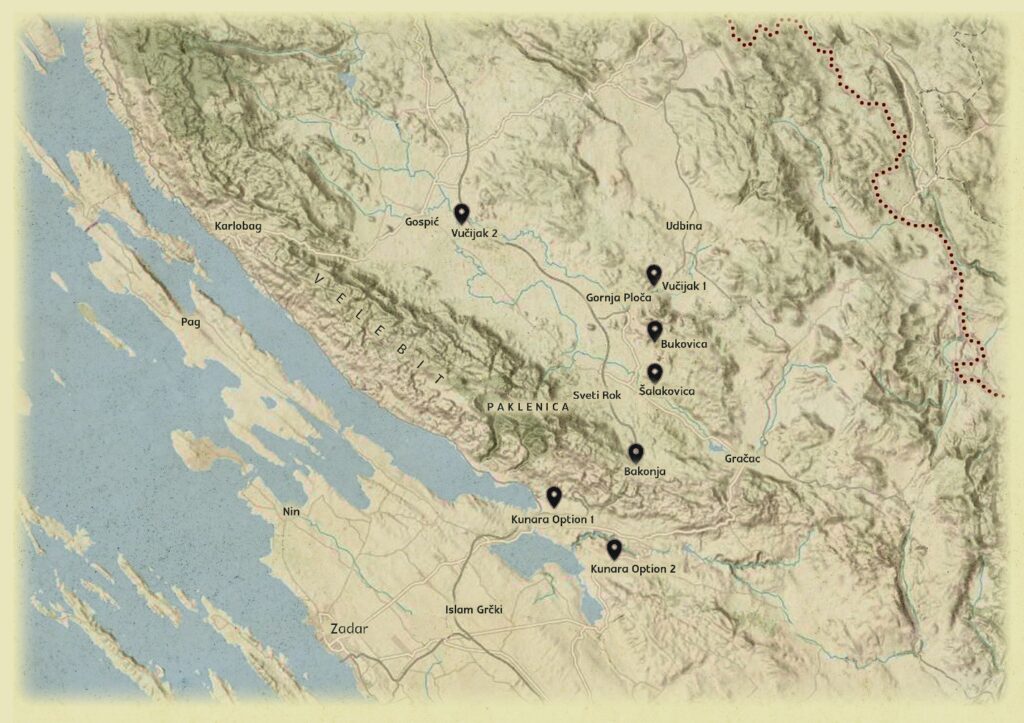

The general rule, though, is that Krajina singers gave accurate itineraries for travel within the Krajina; within its most immediate neighboring region to the south, northern Herzegovina; and across the western border in Kordun and eastern Lika in Croatia. Mental maps of other parts of Bosnia varied by singer, but, in general, they broke down in Croatia toward western Lika, in Ravni Kotari to the west, in Karlovac to the northwest, and in Slavonia (and beyond it, Hungary) to the north. For these often formerly Ottoman-controlled territories (Figure 1 shows the Ottoman/Venetian border around 1650-80, when many of these songs are roughly set), most singers relied exclusively on itineraries passed down through the tradition as well as a basic, shared historical knowledge. Most smaller geographic nodes (villages, lakes, mountains, fields, defiles) in these distant and inaccessible realms are tradition-dependent, highly variable, not easily attributed to real locations, and likely often invented. Even the usually accurate Kolaković has a basic idea of some locations in Hungary but has his heroes take humorously circuitous routes to navigate them (HNP IV.43). Elsewhere his geography breaks down, and he relies on imaginary or difficult-to-identify nodes (HNP IV.49). Many of Marjanović’s other singers filled most of their itineraries with generic names or preferred to forego them entirely when plots extended beyond their geographic experience.

For mountains, the majority of singers knew that heroes traveling from towns like Bihać and Velika Kladuša, in the Krajina, to Udbina, the central city in Ottoman Lika, passed Plješivica

19A systematic refinement of this rough sketch would be valuable for epic scholars but is beyond the scope of this article. The region-focused recordings in the Milman Parry Collection at Harvard would likely provide many answers. Compare with Lord 2019:82.

20 Kolaković is one of a very small number of Krajina singers who accurately noted the historical location of the fortified home of the Christian hero Stojan Janković in the town of Islam Grčki (see HNP III.16, 18; cf. Hadžiomerspahić 1909.1, 8).

150

Mountain.21 Movement from Udbina to the coastal stronghold of Senj demanded traversing Vratnik Mountain, while the choice to head to Zadar instead required crossing Vučjak/Vučijak and/or Kunar/Kunara. If the heroes were in Herzegovina, or the central Dalmatian highlands and headed to Zadar, then they passed either Prolog Mountain or Dinara/Dinar. The traversed order of multiple sites and their relative location in relation to known cities, towns, and bodies of water was often highly randomized with great variation between singers. Individual singers often put

21 Plješivica, Velebit, and Dinara are in reality mountain ranges. Individual mountains, ranges, peaks, and passes all appear in the tradition as singular mountains.

151

the same mountain on an imagined path to towns which are in reality located in highly divergent directions; they also often confused mountains with similar names, such as Korin and Kunar (Marjanović 1898:liii). Translation from the BCMS languages also necessitates anisomorphism—mountains are divided into planine (sing. planina), high and rocky mountains, and gore (sing. gora), low and forested mountains—and singers often differed between their categorizations of the same mountain.

The tradition itself also carried with it the detritus of past iterations and the injection of fantastic elements. Thus, some historical cities or fortresses were placed in highly inaccurate locations by singers who hailed from nearby regions but who no longer recognized the name of the site. There are also a number of mountains, rivers, cities, and even kingdoms which to this day cannot be accurately located and whose status as either fanciful creation or lost historical knowledge remains debated. The city of Janjok/Janok is a notable example that will factor in to the discussion below. In the songs, the city acts as a satellite protecting the border of the Austrian Empire from Ottoman Hungary. While the name historically designates the city of Győr (Detelić 2007:173-74), in epic geography the city’s placement can vary enormously, leading to various designations in past scholarship. Čaušević seems to locate it closer to the city of Odenburg/Sopron (see Figure 2). In the case of epic mountains, some are well known and easily locatable (see Figure 3, where the ranges Velebit, Plješivica, and Dinara are delineated in shadows, and

152

markers designate notable peaks; two suggested locations for Kunara (Kunovac) are also offered). A few have been uncovered through historical research and archaeology (Mimica 2003 and 2008); others have been conjectured by matching peak names to song content (Banović 1923 and 1936). Some have multiple candidates for the original inspiration (compare Figure 6 on Vučijak below); others remain unidentified (for example, Korin,22 Kukara).

Competent singers memorized and consistently redeployed in performance specific itineraries for various directional movement between sites within their songs. This presents a considerable challenge. Not only did these itineraries often include an extended series of nodal points, but also the strict order established in the first singing needed to be retained in subsequent plotting. This made them perhaps even more of a challenge to the singer’s skill than other elaborate, formulaic features of the oral art, such as the traditional themes23 of caparisoning or donning disguises. The scripts (Rubin 1995:24-28) of the itineraries needed to be memorized both forwards and backwards for excursions and return trips. Plot events (such as ambushes,

22 Marjanović (1898:641) discussed Korin as though its location was common knowledge in his day but did not clearly describe it. I am unaware of any scholarly identification of the mountain.

23 As per Albert Lord, “a subject unit, a group of ideas . . . ,” or “a recurrent element of narration or description in traditional poetry.” Quoted in Jurić 2020a:6.

153

skirmishes, or encounters with various characters) often prompted tangential action which disrupted movement through the list and required competent resumption when travel continued. Also, singers often estimated distance of travel on horseback (by hours, days, or nights), and occasionally on foot, between nodal points and injected these assessments into songs. These estimates vary in their relative accuracy, but some singers were quite skilled at this, too.

Another notable addendum to these itineraries, which will factor into the argument below, is the use of a common theme in the Muslim tradition. Epic songs in the wider Western Balkans often include a trope where a hero, crossing a mountain or other wild place, hears animal calls or sounds that startle his horse, which he must then comfort (for example, HNP I.53); let us call it the Animal Call theme. There is a more elaborate, refined, and specific version of this theme sung in the Krajina and Herzegovina. In these, night falls on a traveling hero. He is invariably on the peak of a mountain when this occurs (though exceptions do exist) and most often on the tallest mountain in a specific itinerary; the mountain generally also bears the boundary marker (međa/međaš/mejaš, hunka, or hudut) between two empires. The chosen mountain can shift between singers, but the majority agree. In the Krajina songs, the journey from cities like Udbina and Velika Kladuša to Zadar crosses the imperial boundary on the peak of either Vuč(i)jak or Kunar(a). The two options are often alternatives, though some singers use both, positioning them on separate routes to the coast. In the Hungarian songs, it is predominantly Bakonja that is traversed and that carries the border marker for heroes from Ottoman Buda or Kaniža making their way to Habsburg Vienna or Janjok. In the Western Bosnian Animal Call theme, when night falls, a series of animals—most commonly a wolf, a bear, or a raven, but also cuckoos, squirrels, and other beasts—call out, and the hero must react by calming his horse, traversing ahead despite the frightening atmosphere (for example, Bynum 1979:94-95; KH I.2, II.40; MH III.13; see Čaušević 1888.3, 5, 6); or, in one of Čaušević’s poetic extrapolations, reading the noises as an augury of his army’s fate (Čaušević 1888.4, ll. 3005-49). This central position of Vučijak in the Lika songs and Bakonja in the Hungarian songs is the foundation of Čaušević’s “error.”

Moving Bakonja

Bakonja Mountain appears in five of Čaušević’s eight songs. As Marjanović bemoaned, the singer always places the mountain at the western border of the Lika. He, in fact, gives it primacy in his itinerary for travel between the two most antagonistic centers in the Krajina Songs (Udbina in Lika and Zadar in Ravni Kotari), placing it in the position where most singers used the mountain Vučijak. For Čaušević, Bakonja is a tall mountain (planina), while most other notable peaks along the trail are demoted to low mountains (gore). As with Vučijak for most singers, Čaušević situates the imperial border-marker at or near Bakonja’s peak and most often deploys his Animal Call theme somewhere along its length (Bukovica Mountain takes the honor in song 5).

As we have seen above, Marjanović denounced this anatopism. In fact, there are no less than five points in the MS where he wrote extended comments about this error: how the collector Križević failed to correct the singer; how the quality of the song would be much improved were it not for this glaring mistake; and how best he might go about correcting it for publication.

154

Given the positive support and guidance Marjanović offered in his correspondence with Križević (1888a, 1888b, and 1888d), the frustration in these editorial notes is surprising. This is partly due to Križević’s failure to competently implement Marjanović’s detailed instructions, but it also reveals much about Marjanović’s editorial ethic. In approaching content, Marjanović was trying to understand the dictates of the tradition and to edit in line with them (see Marjanović 1898:liv). The problem, as I will explicate below, was that his scope was myopic. Marjanović was only acquainted with the tradition in the Krajina region, which he extrapolated to all of Bosnia-Herzegovina, a problem that also undermined his critique of Hörmann’s collection (Buturović 1976:68). His devotion to the tradition goes some way toward explaining why the Bakonja problem bothered him so. Marjanović made no attempt to alter the many unknown or imaginary nations, cities, or mountains included in his singers’ songs, nor their use of variant names, shifting of locations, exchanging of mountain names, and other common factual errors, because they were found widely in the tradition and in other published collections (Marjanović 1888a:478 and 1888b:490).24 He drew the line with Bakonja, because the mountain was located in Hungary by other singers according to factual geography. Marjanović was unable to accept an alteration that felt antithetical to both rational logic and the mores of the tradition itself. He attributed the error solely to the ignorance of the singer, never questioning why it was allowed to persist while the singer was immersed in a traditional milieu.

This dedication to the tradition also faltered when Marjanović proposed a remedy to his problem. He recognized that Čaušević was using Bakonja where others generally deployed Kunara or Vučjak; but Čaušević also included those mountains in his Udbina-Ravni Kotari itinerary (see Figure 12, below). While Čaušević’s songs were being considered for publication,25 Marjanović proposed to remedy the Bakonja problem by substituting it for the coastal mountain range, Velebit. This proposition made logical sense. The tail end of the real Velebit range (an area better known today as Paklenica National Park) runs directly through the border between Lika and Ravni Kotari, producing a dramatic descent down to the seaside (see Figure 10). Velebit was used in the epic tradition, but never by Čaušević, so no redundancies would be produced; and Čaušević described Bakonja as a very high mountain, just like Velebit, which contains the third-highest peak in Croatia. This remedy was logical but an affront to the tradition. Here, the editor’s imperative demanded that two wrongs could make a right. Krajina singers do occasionally include Velebit, but consistently locate it (again, as a single mountain and not a range) in a more northerly position, almost always linked to the town of Lički Novi, which is, in reality, at a close proximity to the center of the Velebit massif (HNP III.11, 13, 22, 25; KH II.66; Bynum

24 See, for example, his lenient criticism when Kolaković confused mountain positions (Kolaković 1887/1888b:565).

25 Some of Čaušević’s songs have extensive edits applied to them. Marjanović spent fourteen hours over two days correcting just one of his songs (Čaušević 1888:277), lamenting that still more work was required.

155

1979:391, 394, 407; Majetić 1888.2, 3, 8; Kolaković 1887/1888a.31, 67; Topić 1888.13).26 Velebit is rarely traversed in the songs, almost never on the path from Udbina to Kotari (Bynum 1979:78-96, 391, 394, and KH II.66 are exceptions); and when it is, it is invariably in the songs of bards with messy epic geographies. Mujo Velić, for instance, follows a traditional conception of Velebit’s location in Northern Dalmatia when his hero passes from Udbina, through Vrhovine and Otočac, before crossing Velebit and arriving in Brinje (a reasonable northwesterly progression). At that point, though, Brinje is inexplicably placed on the seaside in Ravni Kotari, 90 kilometers to the south (Bynum 1979:78-96, cf. KH II.66). Surely, Velebit was not the best answer.

Bringing Back Bakonja

Rather than follow Marjanović to hasty reproach and editorial intervention, let us return to Čaušević’s songs; bring Bakonja back to the Lika/Kotari border; and ask how it got there and why it was allowed to stay in the span of four years spent performing in a traditional singer’s milieu. The first step in approaching the problem is to understand the idiosyncrasies of Čaušević’s singing.

We can infer that Čaušević was not well versed in the wider geography of the Western Balkans. This, of course, makes sense for an illiterate peasant in one of the poorest regions of Bosnia, let alone one incarcerated at the age of eighteen. Križević (1888a:2) reveals that Čaušević learned some songs in Mutnik, a village due north of Brekovica near the town of Cazin. However, his song geographies suggest this was the zenith of his peregrinations before his arrest. His epic verse need not take us to Dalmatia or Hungary to offer geographic inaccuracies, but only thirty-three kilometers north to the nearby city of Velika Kladuša. Čaušević’s third song, Mujo Hrnjica and Babić Husein, is a multiform of a common song where the famous Mujo and his oath-brother compete to travel to Malta and kidnap the daughter of the Island’s Ban (“Viceroy”) as a quest to decide who will marry the Bosniak maiden both have been courting. After the stakes have been set, Mujo returns to his home in Kladuša to dress in Christian disguise and set off for Malta. Before traversing the boundary between the Krajina and Lika, though, Mujo goes on this rhetorically linear but geographically circuitous excursion: Velika Kladuša → Šturlić → Tržac → Liskovac selo → Cetina (Figure 4). Šturlić, Liskovac, and Tržac are names known to Čaušević, but their spatial relationship to one another is unclear. On the other hand,

26 Mirjana Detelić (2007:62-64, 291-92) assigns nearly all examples of the name Novi/Novin/Nović in epics to the city of Bosanski Novi. This seems to be more a feature of the Christian than the Muslim epics. In the latter, Novi denotes Bosanski Novi in some instances (HNP III.14; KH I.22, 24, II.61 (uncertain)) and Herceg Novi in others (MH III.17, 24, 25; KH II.66) (which may also be Lički Novi (Buturović 1992:17)), but I am convinced that the majority of Muslim songs featuring this name refer to Lički Novi (for example, HNP III.10, 11, 13, 21, 22, 24, 25, IV.33; KH I.27, 33, II.61 (uncertain), 62, 66; Hadžiomerspahić 1909.4; Čaušević 1888.3; Islamović 1888.36; Kolaković 1887/1888a.31, 48; Topić 1888.13), which was also a well known center in Ottoman Croatia. Elsewhere, Detelić locates the epic town of Brežina/Brežine as Brezine near Pakrac, Croatia (2007:70). She suggests this explanation works only if we ignore Brežina’s connection to Janjok, but also forgets its connection to Bakonja (for example, HNP IV.43) which, combined, may recommend a Hungarian location.

156

Cetina (today, Podcetin/Cetingrad; see Detelić 2007:87) is not a known site for him. He assumes that it is located south toward Bihać or Željava but has, in fact, nearly returned his hero home.

Knowing that the singer’s personal knowledge of geography was limited to his close surroundings in the Bihać area, we can first understand that he was entirely dependent on the songs for his itineraries. This means that Bakonja was as abstract a place to Čaušević as were Malta, Zadar, and likely even nearby Karlovac and Udbina. A Krajina performance milieu, however, should not have taught him to put Bakonja on the path to Zadar. Marjanović’s star singers like Mehmed Kolaković, Bećir Islamović, Ibro Topić, and others were all from the wider Bihać region but never made this error. Even the singer Hasan Majetić, from whom Marjanović collected eight complete songs and whom Čaušević noted as a teacher and the source of half of his collected songs, never makes this substitution. Whence this habit, then? A survey of the wider sphere of Bosniak epic singing provides part of the answer. Čaušević’s artistic lineage must pass through either his father (and brother), or else Ahmo Samarđić, Omer Ukić, or some other unnamed influence,27 and thence south to the region of Herzegovina.

27 Čaušević named the source of all but one of his songs to Križević. He noted only one song he learned from Ukić, and he did not count him among his teachers. That said, the song he learned from Ukić includes the Udbina-Kotari itinerary. Marjanović collected only one song from Ukić (1886), leaving his repertoire a mystery. Thus, he cannot be ruled out. There is no collected material from Samarđić, though the recorded song he taught Čaušević does not include this itinerary. Singers also often credited notable locals as their teachers for reasons of prestige (Bynum 1979:7-8), or could count anyone from whom they received a song as a teacher. The exact source is open to much conjecture.

157

A Herzegovinian Tradition?

The Hörmann collection contains two songs from Mostar (KH.27 and 61) in which Bakonja is situated in Lika. Song 27, Mustajbeg of Lika Pillages Zadar, mirrors Čaušević’s songs in putting Bakonja on the path from the character Lički Mustajbeg’s home (here, Novi rather than Udbina) to Zadar. This song is of a very poor quality, and Marjanović competently critiqued it in his review of the collection (1888f:559), although he surprisingly made no mention of Bakonja’s shifted location in the song, nor, it seems, remembered that fact when he began to edit Čaušević’s songs. Song 61, The Wedding of Ahmed-beg, the Vezir’s Son, also positions Bakonja in Lika but, presumably, in a more northerly position. Here, the mountain is placed near

the city of Novin/Novi (presumably Lički Novi, maybe Bosanski Novi, but in both cases highly inaccurate; Figure 5 roughly estimates the position using Lički Novi); heroes returning from Buda traverse it to arrive at Novi. It is notable that this singer, too, seems to have a poor grasp of geography, with Buda and the river Drina imagined to be very close to the Krajina (ll. 360-68, 662-64). Another two Herzegovinian singers situated Bakonja roughly in the Banovina region or

158

somewhere within the traditional Croatian Kingdom. Vuk Vrčević offers a song collected from one Memed-aga Šilović from the village of Trebinje, in which a hero leaving Velika Kladuša crosses Kunar, Bakonja, and Prolog Mountains on the way to Janjok (2010.30). A Romani smith, Meho Morić, from the village of Rotimlja near Stolac, related another song to Alija Nametak in 1926, in which an exceptional geographical divide separates the cities of Velika Kladuša and Karlovac (1991.8). This path can be taken scenically through a series of mountains (ll. 106-48) or condensed with a quick journey over Bakonja (ll. 331-33). While all these Herzegovinian singers gave unique and often vague positions to Bakonja, they were consistent in placing it well below Bakony’s true position in Hungary, generally locating it between Zagreb and Zadar.

There is further support for the assertion that Čaušević’s singing was influenced by a Herzegovinian artistic lineage. Returning to the Animal Call theme, in Čaušević’s songs, the heroes passing over Bakonja not only hear the frightening calls of various animals, but Čaušević also includes vilas—the female supernatural beings that regularly figure in epic song (Jurić 2019b and 2023b)—that fly across the path above the hero (Čaušević 1888.4, ll. 3010-14. See esp. Jurić 2019b:139-42):

S desne im strane zavijaše vuci

A čuju se mrki gavranovi,

A pjevaju orli mrcinjaši,

Preko puta prelijeću vile,

A čuju se tice uranjkinje.

From their right side wolves howled,

And dark ravens could be heard,

Scavenger eagles sang out

Vilas flew across the path,

And early morning birds could be heard.

This addition is not found among the Krajina singers, but it is found in a song from Zagorje in northern Herzegovina (KH I.2, l.1236). An even stronger case could be made for a Herzegovinian source for vilas in the Animal Call theme if we had better collection data for the songs collected by the early Bosnian folklorist Ivan Franjo Jukić, who featured a song with this motif but without regional ascription (Jukić and Hercegovac 1858.21, ll. 162-65).

Jukić’s failure to denote collection locations affects another possible source of evidence regarding yet another mountain. One of the most common of what could be called the second-tier mountains employed by Krajina singers is Lašakovica (perhaps derived from the town Laškovica near Skradin). It appears twice in Marjanović’s edited volumes in one song each from Mehmed Kolaković (HNP III.16, l. 378) and Bećir Islamović (HNP IV.30, l. 84). Both singers pair it with the mountain Bukovica (literally “Beech Mountain”), which is passed before Lašakovica, and both employ a general rule that the mountain belongs in songs connected to the historical city of Cetina (in the Dalmatian highlands near the city of Kijevo) (Detelić 2007:86-87). That said, Kolaković situates Lašakovica in his itinerary as the last mountain crossed before reaching Ravni Kotari, while Islamović places it between Cetina and a not-easily-identified city of Selencija. The mountain appears infrequently enough in songs that it is difficult to say which of the two singer-provided locations, if either, had the broadest consensus in the tradition. The name, though, likely provides further evidence that Čaušević’s artistic lineage lay outside the Krajina. Čaušević used Lašakovica Mountain in his Udbina-Kotari itinerary, but, for him, the mountain’s name undergoes metathesis, becoming Šalakovica. The only other mention of Šalakovica in published collections is in a song from Jukić’s collection, though it is found in a messy itinerary (1861.40,

159

l. 458). Here, too, it is appended to Bukovica. It cannot be corroborated, but I am convinced that the two songs from Jukić were collected in Herzegovina and that they add further support to my assertion about Čaušević’s artistic lineage.

A convincing case can be made that presents Čaušević as a young singer, still perfecting his craft, who adopted his Udbina-Kotari itinerary from a regional tradition adjacent to, but removed from, his native home. With added geographic distance, and following the kernel of useful truth in Jovan Tomić’s observations about diminishing geographical accuracy in epic (Jurić 2020a:22-23), we should expect songs produced in Herzegovina to be less accurate regarding northern locations than in the Krajina.28 What seems at first glance a very minor revelation, in fact allows for the fault of the “error” to be hung on the tradition rather than the individual singer. This frees analysis to approach Čaušević in the terms of the tradition itself using emic criteria.

Čaušević’s Itinerary

Despite the misplaced mountain within it, Čaušević’s Udbina-Kotari itinerary is largely consistent (see Figure 12). Nearly every one of his songs involves travel from Udbina to Ravni Kotari or vice versa. Many are bookended with travel within the Krajina, Lika, or Kotari regions, which sometimes include flawed geography (most notably the example in Figure 3), but which are roughly in line with the mental maps of most competent singers. Once action is concluded in the Krajina, the heroes generally access Čaušević’s pipeline to the coast through Udbina or Lički Ribnik by traversing the first mountain in his itinerary, Vučijak. Vučijak (literally, “where the wolves are”) is a common name for Western Balkan mountains and peaks. Figure 6 displays all sites in the Lika that bear this name (most data are drawn from Borovac 2002:462), including Stipan Banović’s favored site for the epic Vučijak, Vučjak-draga just west of Krupa (Banović 1923:339; number 12 in Figure 6). My research, however, points to a feature in the Velebit range, Vučja draga (number 10 in Figure 6), today above the north entrance of the Sveti Rok tunnel, which fits perfectly most singers’ placement of Vučijak and Čaušević’s description of Bakonja.

This placement is also surprisingly consistent with the historical Venetian-Ottoman border of 1683, after the Ottomans were pushed out of Ravni Kotari (see Figure 7). Čaušević’s exact placement of Vučijak is inconsistent but explicable. He most often places it within visual range of Udbina (Čaušević 1888.4, l. 2527) on the path to Zadar, likely imagined near the real village of Kurjak. There is, however, one song (Čaušević 1888.7) where he moves the mountain to a location in between Budak and Lički Ribnik, somewhere near the city of Gospić (see Vučijak 2 on Figure 12). This is a direct borrowing of the mountain’s placement from Hasan Majetić (1888.2) who taught the song to Čaušević. Čaušević did not recognize the incongruity, since these foreign places were utterly unknown to him.

After Vučijak has been passed, three mountains are then offered in succession: Bukovica → Šalakovica → Bakonja. Out of nine complete trips in Čaušević’s collected repertoire, the

28 Marjanović notably predates Tomić’s conclusions (Marjanović 1888b:491). Note, also, that the Krajina singer Murat Žunić was critical of Herzegovinian singers because “they made mistakes in [Krajina] geography” (Lord 2019:23).

160

mountains take this order in five (in songs 4, 5, and 6). In two other journeys, he confuses the order without cause, shifting it to Bakonja → Bukovica → Šalakovica (in songs 1 and 2), whereas, in another two journeys (in songs 4 and 6), he retains his conventional order despite the direction of travel having been reversed. The latter mistake is commonly explained by an over-reliance on rote repetition, while the former is a simple error in performance. Even in one song (song 5) where the point of origin is the city of Knin rather than Udbina, Čaušević deftly adapts his itinerary. The heroes leave Knin, pass over Dinar Mountain (which is proximate in reality, although in the opposite direction), and thence access Bukovica, skipping Vučijak as a unique entry point from Udbina, to continue the common course of travel to the coast.

Once these three mountains have been traversed, Kunara Mountain consistently serves as the exit point into Ravni Kotari (it is only forgotten in one of four trips in song 6), much as Vučijak does for Udbina. In all recitations of this itinerary, Bukovica and Šalakovica remain on the Lika side of the border, while Bakonja exclusively is bisected by the imperial border. Across all songs, Čaušević retains the categorization of Bakonja and Kunara as high mountains (planine), while Vučijak alternates between high and low (gore), and Bukovica and Šalakovica are (except one instance for Bukovica) kept as low mountains. Čaušević could not have known this, but his system suits the real topography as the Lika’s forested grasslands and low mountains

161

break into the karstic peaks of Velebit (see Figures 8-11). Placing Kunara in closest proximity to Ravni Kotari (two options are given in Figure 12) is also a common practice in the epic tradition and lends some added weight to a speculated real-world site (see Kunovac 2 in Figure 3, above).

Having taken up an emic set of criteria for assessment, we find that Čaušević does quite well with his geography. He does not prove himself an exceptional singer in this regard; but, given his age and the relatively short time he spent immersed in a traditional milieu, his mental mapping and itineraries are actually quite impressive. While he does move Bakonja from its proper place in Hungary down to the Lika/Kotari border, his constant grouping of Bukovica, Šalakovica, and Bakonja in succession serves as proof that he has not muddled the itinerary of

162

163

164

his Krajina peers but, rather, borrowed the entire set as a package from the singers who first taught him the art. He is thus serving the central ethic of the traditional epic singers: to faithfully reproduce the songs as he learned them (Lord 2019:27-29, 105). It is my contention that, while Čaušević’s songs were characteristic of the Krajina, the lineage behind his first itinerary derives from Herzegovina, a region where Bakonja was clearly as fanciful a mountain as Lašakovica and where none would question why it was located near Zadar.

We can imagine that, had Čaušević never committed his crime, and had he remained in Brekovica, he would have progressed as a singer. Other singers, having heard him perform, might have felt that his use of mountains in his songs seemed incorrect, but likely would not have publicly or personally critiqued him, since both Bakony and Ravni Kotari lay in territories most had never visited: any unease would be tempered by doubt. If pressed to comment on the discrepancy, most singers would have likely deferred to the wisdom of the tradition and retorted in a similar manner to Mehmed Kolaković: “I sing [the song] as I heard it and learned it” (Marjanović 1898:xv). Čaušević may have grown to respect a local singer as a model and altered his mountains (“the corrective influence of the tradition” (Lord 2019:126)), his community of reception might have debated his mountains (see Honko 2000:27-28), or he might have held stubbornly to the itinerary as he was taught, defending its accuracy. Perhaps this is exactly what he did after he left KPZ in 1891 and regained his freedom, but we will likely never know. What is certain, however, is that Čaušević’s placement of Bakonja was perhaps perplexing but apparently traditional, even if Marjanović did not recognize it as such.

The Editor’s Imperative and Epic Geography

Understanding Marjanović’s problem with Čaušević’s songs helps us to grasp an unspoken principle in academic analysis of epic before the work of Matija Murko, Milman Parry, and Albert Lord. Marjanović was an exemplary collector for his time regarding the care he spent in trying to understand the logic of epic songs and their traditional artistic context. This was a legacy he actively cultivated following his predecessors, particularly the groundbreaking work of Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, whom Marjanović used as a model (1888a:478, 1888b:488, and 1888c:510). The ability and desire to guide the scientific endeavor towards a complex and complete understanding of the logic of the tradition was, however, not fully formed. Although the approach was debated among academics of the time,29 the continued demand to see oral traditions as national literature rather than a folk art meant that a biased, belletristic criterion of quality continued to be applied to the songs. While the greatest singers could come close to that aesthetic, all required some level of “help” from the editor to achieve it. A similar, and yet in many ways oppositional, perspective demanded of the songs that they always serve an educational role as the primary vehicle for historical knowledge in a folk milieu. Here, too, the songs of the best singers came very close to history—and, with it, geography and topography—but all needed editorial intervention. Oral epic is in many ways a rough blending of these two functions, but one based on a logic and a set of expectations that are unique and particular to the

29 Marjanović’s drastic editing was notably challenged by a colleague at Matica (Buturović 1992:571-72).

165

art form. Even from the earliest times, we know that epic was only one of very many vernacular arts, didactic practices, pedagogical systems, and social models by which immaterial cultural products and historical knowledge were shared or passed down. Epics existed in an ecosystem alongside religious sermons; church art; instruction in mektebs (مکتب, Islamic religious primary schools); work songs; oral and written chronicles; “telling tavarih” (Jurić 2019a:20); and oral prose narratives of various genres.

Folklorists of the nineteenth century strove to grasp the workings of the epic tradition, but the simple recognition that there existed singers of varying skill and songs of varying quality or accuracy meant that theoretical paradigms like the degradation model allowed for positing an original “perfect” version that was corrupted by lesser singers or by temporal and spatial transmission.30 This often became tacit permission for carte blanche approaches to editorial work, so long as the changes were seen as judicious and sparing—Marjanović is the prime example of how subjectively that could be interpreted—and so long as alterations were deployed in the spirit of the art form. Four lines of text might be rewritten as two, so long as they were retained from the original cola. Lines might even be produced out of whole cloth, provided they mirrored the style, meter, and tone of other lines.