Oral Tradition, 37 (2025):3–18

Introduction

This article examines an apparently undocumented tale from northwestern Africa: a short, simply phrased dialogue between a man and a cat. The cat finds some money, and repeated questions of “What do you want that for?” lead to progressively longer-term goals, outlining a moderately successful life. These goals are largely constant across different versions, except for the final goal, which no two attested versions share, letting the narrators use it to present their own take on the purpose of life.

As the description may suggest, this is a chain tale—a tale in which each successive episode triggers another parallel one, building up a “chain” of events linked by cause and effect, like “The Gingerbread Man” or “The House That Jack Built.” A number of chain tales worldwide and in North Africa seem to involve cats; the progression towards success in this one vaguely recalls the well-known European tale “Puss in Boots.” The way in which each item is used to achieve the next somewhat recalls various tales of Lending and Repaying (ATU 2034C; Uther 2004:II, 700), but most steps here involve neither lending nor payment. The most similar case found while searching the literature is perhaps El-Shamy’s (2004:959) type 2018§, “Economic Cycle: One Commodity Needed, but it is Owned by Someone Else who Requires Another Commodity” (I thank El-Shamy for pointing out this parallel), but the Egyptian nursery rhyme that exemplifies this pattern involves quite different characters and commodities. Notwithstanding such thematic resemblances, the tale under discussion seems to be missing from standard folktale indexes, suggesting its absence outside the region; notably, it is not to be found in Uther (2004), nor in El-Shamy (2004), nor even in Taylor (1933). Nor has it been observed in collections of Berber tales consulted, such as Laoust (1949) or Stroomer (2002 and 2003) for Morocco; Bellil (2006), Delheure (1989), and Lafkioui and Merolla (2002) for Algeria; Stumme (1900) or Ben Maamar (2020) for Tunisia; and so forth.

All versions of this tale found so far come from a rather specific part of southeastern Morocco and southwestern Algeria: the precolonial range of the Ayt Atta (Ayt Ɛṭṭa) (Hart 1984:5–7). The Ayt Atta confederation first emerged around Mt. Saghro in the Anti-Atlas, tracing their descent to a sixteenth-century ancestor named Dadda Atta. After founding their traditional capital, Igherm Amazdar, they began expanding beyond this region, becoming a major force in regional politics in the seventeenth century. By the nineteenth century, their influence extended

3

across a wide area: northwards to the Dades valley and beyond, westwards to the Tafilalt valley, southwards through the Draa valley, and into the Sahara as far west as Tabelbala and even Touat. In the oasis of Tabelbala in southwestern Algeria (Champault 1969:32), they encountered and, in the case of those who settled down there, ultimately switched to a language that was just as different from their own Tamazight (Berber) as it was from the dialectal Arabic they often learned as a second language: Korandje, a geographically isolated Northern Songhay language brought north from Niger during the medieval period (Souag 2015; Souag 2010).

Four versions of this story are attested so far, at the northwestern, southwestern, and southeastern extremities of this vast territory. Two are from Tamazight, in southwestern Morocco. The first is an abbreviated version recorded in Rabat in 1907 by Biarnay (1912:359) from a traveler named Lhasain ou Mohammed, who came from the ksar (fortified village) of Tiselli near Boumaln in the Dades valley. The second is a fuller version recorded in 2012 by Amennou (n.d.) from a fourteen-year-old boy, Rachid Amadin, in the village of Taḥramt near Tagounite in the Draa valley; Amadin had heard the story from sixty-five-year-old Lalla Zahra Brahim. (I thank Amennou for permitting me to use this as yet unpublished material, and for pointing out its connection with Biarnay’s version.) The other two versions are from Korandje. One, recorded by the author in 2007 from B. Belaidi, is from Ifrenyu (Cheraia), a village in Tabelbala largely inhabited by the Ayt Isful (in Korandje: It Sful) subgroup of the Ayt Atta. The other was recorded by Champault (1950) from Zohra Adda (whose name was variously transcribed, notably as “Zorah Assa”) and subsequently transcribed and translated by Souag.1 While Champault provides no details on her origin, her pronunciation, in particular her fronting of the vowel in /ka/, suggests that she was from Ifrenyu’s rival village, Kʷạṛa (Zaouia), which is not inhabited by the Ayt Atta. No available evidence suggests that either of the Korandje speakers could speak Tamazight (Belaidi certainly could not), still less that either of the Tamazight speakers could speak Korandje (which would be very unlikely given their locations); bilingualism in this context would normally involve the regional lingua franca, Maghrebi Arabic. The story is absent from the short collections of Ayt Atta tales gathered by Hart (1984:113–16) and Amaniss (2009:723–47).

1 The present author’s transcription, morphemic analysis, and translations into English and French are available, along with the original recording of the story, at https://doi.org/10.24397/pangloss-0008021.

4

2. Form

The attested variation in this tale allows its development over time to be better understood, in accordance with the general principle that innovative changes to an already widely known tale are are more likely to be heard by people nearby than by ones living far away, and hence are more likely to be passed on locally than to spread further. Similarities in wording across and within the two languages permit a more precise understanding of how it was memorized and transmitted.

2.1 Phylogeny and Reconstruction

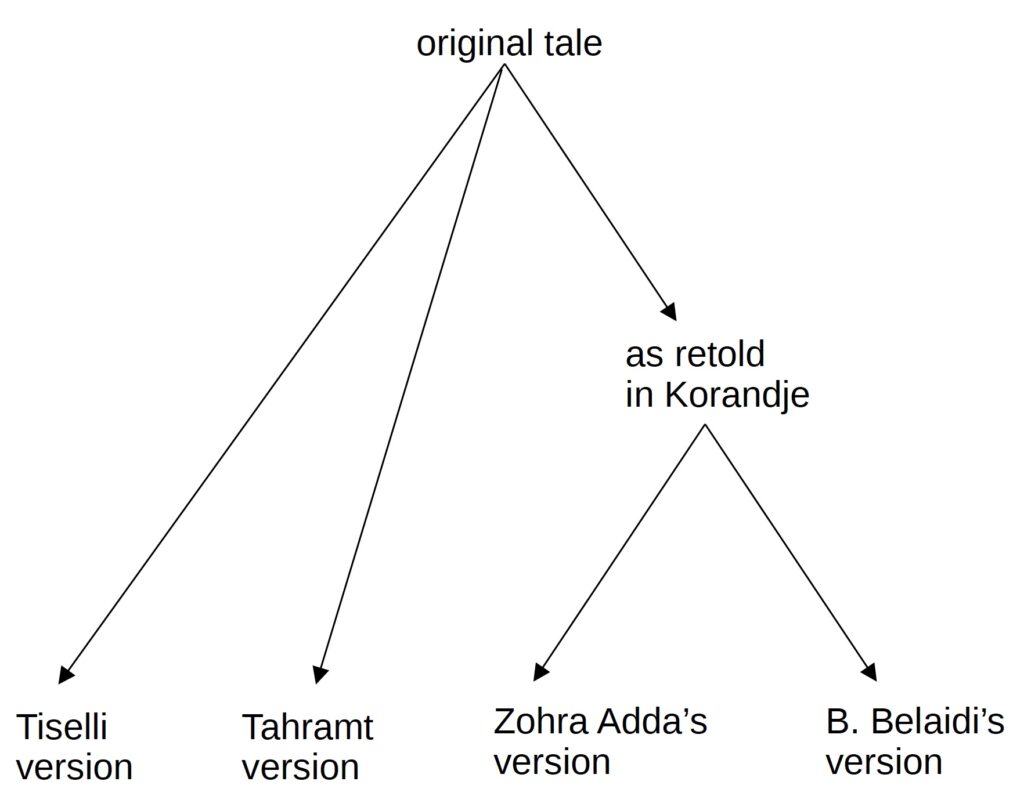

Phylogeny is the study of evolutionary/genealogical history and relationships. The term was originally coined for biology; in the context of folklore, such study has historically been better known as the historic-geographic method, traditionally associated with the Finnish School (Frog 2013). This approach fell out of favor in the late-twentieth century, as attention shifted towards synchronic analysis, only to reappear in recent years with the application of quantitative phylogeny to the study of folktales (see, for example, d’Huy 2013; Graça da Silva and Tehrani 2016). It appears unnecessary to apply quantitative methods here; with only four versions to examine, qualitative methods are sufficient to yield results. The transmission of folktales is not in general amenable to a strict tree model, since tales need not be copied “vertically” from a single source, and can easily “horizontally” combine elements from multiple sources. However, in the specific case of the tale under discussion, a tree model turns out to account adequately for the attested versions; there are no indicators of hybridization or contact between branches.

Each attested version is slightly different from each of the others (see the Appendix). The closest parallels are, unsurprisingly, found between the two Korandje versions; while Belaidi omits the opening formula and prologue, his dialogue is nearly identical to Zohra Adda’s, apart from the omission of “bricks” (4b–5a). The Korandje versions, in turn, are clearly more similar to

5

the Tamazight version from comparatively nearby Tahramt than they are to the story from the more distant village of Tiselli. The Tahramt version is only slightly less elaborated than the Korandje one, omitting “clay” (3b–4a), “milk” (9b–10a), and “ghee” (10b–11a), and (uniquely) slightly rationalizing the scenario by attributing the answers to the man’s mouth rather than to the cat. The Tiselli version, on the other hand, drastically reduces the chain to a bare minimum—“money” (2a) > “house” (5b) > “children” (7b)—perhaps simply reflecting difficulty in recollecting the whole chain. The curious choice of “figs” as the final goal (11b) might be an agriculturally oriented substitution for “milk” (recalling that figs have milky, white sap, and that, being farther north and better watered than Tabelbala, Tiselli is presumably a better place for growing figs). Both Tamazight versions contrast with Korandje in their prologues, where the cat finds money rather than merely looking for it (0d), and in making “children” an explicit part of the chain rather than an implicit one (7b–8a); in these respects the Tamazight versions must reflect the original, insofar as their content is implied by the rest of the tale. This means that, despite the apparent areal similarities between the southern versions in contrast to the northern one, the only identifiable shared innovation is between the two Korandje versions, yielding the following phylogenetic tree for the transmission of the tale:

In light of the proposed phylogeny, the narrative (or scene) may be reconstructed as follows:

(0a) [Opening formula] (0b) There was a cat and a person. (0c) The cat scratched around, (0d) and found some money. (1a) The human asks for the money. (1b) The cat refuses. (2a) “What do you want money for?” (2b) “To buy a donkey.” (3a) “What do you want a donkey for?” (3b) “So I can

6

transport clay.” (4a) “What do you want clay for?” (4b) “So I can make brick.” (5a) “What do you want brick for?” (5b) “So I can build a house.” (6a) “What do you want a house for?” (6b) “So I can put a married couple in it.” (7a) “What do you want a married couple for?” (7b) “To bear children.” (8a) “What do you want children for?” (8b) “So they can herd the herd for me.” (9a) “What do you want a herd for?” (9b) “So I can get milk.” (10a) “What do you want milk for?” (10b) “So I can make ghee.” (11a) “What do you want ghee for?” (11b) [A final goal, different for each speaker] (12) [Closing formula]

2.2 Opening and Closing Formulae

The two oldest versions are both framed by formulae—an opening formula from Zohra Adda (Tabelbala), and a closing one from Lhasain ou Mohammed (Tiselli). That fact suggests that the formulae were original; their omission in more recent recordings may reflect the decline of the practice of oral storytelling. However, with only one attestation each, their content cannot safely be reconstructed on the basis of this story alone, and would in any case most likely have been determined by general local practice rather than being specific to this tale. The opening formula attested is a literal translation of the widespread Maghrebi Arabic opening formula ḥajit-ek ma jit-ek, “I have told you, I have not come to you,” also used in Eastern Moroccan Berber (Kossmann 2000:75). The closing formulae fit into a wider North African schema where the narrator leaves the scene of the tale to rejoin the audience (“I left them in misery and came in peace”) and then gets the best of the food (“The marrow of the bone is for my mouth, and the dirty innards for the gathering!”), as in the Moroccan Arabic formula, “I passed from there and I returned; I brought a load of cucumbers and a load of sandals; until tomorrow morning, and I’ll give you your part, O you who have not eaten” (ibid. 75). The usual Korandje closing formula ɛakks nis ṭạz fʷ kadda mʷec anɣa, “I left you a little couscous, the cat ate it,” corresponds to the second part of this closing schema.

2.3 Recurrent Linguistic Structures

All four versions of the tale use the same construction for the questions: “what want[second-person singular perfective] N?,” in the sense of, “what do you want N for?” In Korandje, this construction is not particularly common, and was not observed outside of this tale; one would normally expect maɣạ n-bəɣ N, that is, “why do you want N?,” or the like. The form ma used by Zohra Adda is otherwise normally used in modern Korandje only to form rhetorical questions, like ma kʷənna-ni, “what’s wrong with you?” Both aspects suggest a tale-specific calque into Korandje from a Tamazight original, providing further evidence that, as suggested by the phylogeny above, this tale was first told in Tamazight.

7

| Gloss | what? | want[second-person singular perfective] |

| Korandje (Kʷạṛa (?), Z. Adda) | ma | n-beɣ ____ |

| Korandje (Ifrenyu, B. Belaidi) | tuɣ | n-beɣ ____ |

| Tamazight (Tahramt) | may | t-ri-t ____ |

| Tamazight (Tiselli) | ma | t-ri-t ____ |

| Translation | What do you want ___ for? |

The replies are mostly purpose clauses (marked with ad + aorist/imperfective morphology in Tamazight, irrealis -m- in Korandje), usually with a first-person singular subject (-ɣ or ɛa-,respectively), followed by a direct object which serves to motivate the next question. Tamazight allows a choice between the aorist and the imperfective in the context of purpose clauses like these, making it possible to mark some actions in the chain (“scratch,” “put/bear children,” “tend the herd,” “give figs”) as durative. This contrast is neutralized in Korandje, which shows the irrealis (corresponding to the Berber aorist) throughout, except insofar as Belaidi usually substitutes prospective -baɛam-, “going to, want to” (whose m in turn derives historically from the irrealis).

In many cases the verb is also combined with an enclitic pronominal adpositional phrase, following ad in Tamazight and simply following the verb in Korandje. Two of these serve to indicate the role of the immediately preceding chain object in the new action: “with it/them” (is in Tamazight, ndzi in Korandje), “in it” (dis, aka). The third indicates the role of the speaker in those clauses whose subject is not the first-person singular: “for me” (iyi, ɣeysi).

2.4 Chain Elements

Any chain tale poses the formal challenge of remembering a relatively long ordered list of events. In general, oral literature is rarely if ever memorized verbatim (Lord 1991:22), but specific aspects of form are often remembered, particularly when supported by a surface schema, such as rhyme, that could aid narrators in remembering specific words (Rubin 1995:70). In this case, we have already seen that the repeated idiosyncratic question construction seen in the previous section is reproduced perfectly by three out of four speakers, implying that it was remembered rather than being reconstructed based on the gist. Comparing the sequence of replies across the four versions casts some light on how far the remembering of form extends in this case.

The direct objects in the chain match in meaning but not in form, both among the Tamazight versions and between them and Korandje. The only item cognate across both languages is ạḍḍeb/uṭṭub, “brick,” which in both languages is the only generally used word for the concept. Within Korandje, however, the nouns chosen are identical (when present) in every case across both versions.

8

| Korandje (Kʷạṛa?, Z. Adda) | Korandje (Ifrenyu, B. Belaidi) | Tamazight (Tahramt) | Tamazight (Tiselli) | |

| money | idṛạmen | idṛạmen | arryal | aqqariṭ |

| donkey | feṛka | feṛka | aɣyul | |

| clay | labu | labu | ||

| brick | ạḍḍeb | uṭṭub | ||

| house | gạ | gạ | taḥanut, “room” | tigmmi |

| the couple | muḥemmed ndza fạṭna, “Muhammad and Fatna” | muḥemmed ndza fạṭna, “Muhammad and Fatna” | tislatin, “daughters-in- law” | |

| children | arraw | ifrxan / arraw | ||

| herd | tawala | tawala | iɣjdn, “goats” | |

| milk | huwwa | huwwa | tazart, “figs” (see discussion in section 2.1) | |

| ghee | gi | gi |

The verbs in the chain behave rather differently. Between the two Korandje versions, the verbs show much less consistent lexical choices than the nouns, agreeing less than half the time. Across the two Tamazight versions, on the other hand, the verb choices are more consistent than the nouns, agreeing in three out of four cases. In two of these three cases, Zohra Adda uses the Korandje verb which corresponds most literally to the Tamazight one, while Belaidi uses a less semantically similar verb.

| Korandje (Kʷạṛa?, Z. Adda) | Korandje (Ifrenyu, B. Belaidi) | Tamazight (Tahramt) | Tamazight (Tiselli) | |

| scratch | yinbec | mrrq, “crawl” | xbṭ | |

| find | tellạ, “look for” | af | af | |

| buy | dzay | dzey | sɣ | |

| transport | neggeṛ | negger | asi | |

| make | kạ | |||

| build | kikey, “build” | ikna, “make” | bnu, “build” | bnu, “build” |

| put | dza, “put, do” | gwạndza, literally “cause to sit/stay” | g, “put, do” | g, “put, do” |

| bear | arw | |||

| herd | israḥ | saḥ | ks | |

| milk | kaw, “take out” | ṣạ | ||

| make (butter) | kaw, “take out” | ikna |

In short, if we confine our attention to versions other than Belaidi’s, the verbs largely match

9

verbatim within Tamazight and correspond to their expected literal translations in Korandje, whereas the nouns show no consistency across narrators in form even when they match perfectly in meaning. Yet comparing Belaidi’s version to these three, the opposite appears: the nouns in this version match verbatim with Zohra Adda’s older version, whereas the verbs frequently differ.

In general, verbatim matches like these are most economically explained as a side effect of remembering meaning alone. However, where synonyms and near-synonyms are available (for example, “build” vs. “make,” above), it may prove necessary to explain them as the result of remembering forms, as well. To the extent that the latter may hold, the difference observed would suggest a difference in the role of form within the representation in memory of the chain. The general pattern would then be for each action in the chain to cue a remembered verb (the semantic head of the phrase); the exception, exemplified by Belaidi, is for each action to correspond to a remembered noun (and thus to the end of the phrase, expected on general grounds to be more memorable than the middle). To confirm or disprove this pattern, it would be necessary to compare more versions of this story.

3. Function

No available data bears directly on how this story was used in practice; given the obsolescence of traditional storytelling, such data may already be impossible to obtain. (In Tabelbala, while I was sometimes able to elicit stories by asking for them directly, I never witnessed a spontaneous storytelling session, and I was repeatedly told that the arrival of television had led people to abandon the habit. One may hope that such claims are slightly exaggerated, but they correspond well to patterns observed elsewhere in the region.) However, reasonable inferences as to the original purpose of this story may be made from its content and from the observed variations in it.

Any chain tale can be considered to train children implicitly in list memorization and in recursive reasoning. This one, however, evidently has a more specific purpose. In any of its versions, it explicitly sets forth an example of longterm life planning, where a remote strategic goal is realized by executing a long sequence of intermediate tactical goals, ultimately making a small initial investment of effort yield a large return. The inference seems clear that, like so many other animal fables, it was intended to be instructive. It not only suggests a life plan for the child to adopt—to invest money and work hard until they have grandchildren—but also implicitly reveals the child’s place in the life plan of the adults around them: to support them in their old age. (Stories like this would most frequently have been told by elderly women to young children of the household, making this moral particularly relevant.)

The nature of this life plan is clearer when interpreted in its social context. This region, like North Africa more generally, is characterized by a patrilocal joint family structure (Tillion 1973; Hart 1984:94), in which an adult son brings his bride into his father’s household upon marriage to form a three-generation household. In this context, marrying one’s sons off (6b) is an economically consequential decision. It requires an initial investment by the father—building a new room, or a new house (5b), as well as paying for the wedding (Hart 1984:91)—but brings longterm returns by increasing the household’s labor power (7b), allowing it to care better for its

10

herds or its orchards (8b), which may hence yield more (9b). All versions of the story thus also prepare its listeners to understand their future roles in such households as beneficial to themselves and their families. It is perhaps symbolically relevant that the substance usually cited in (9b)—milk—is not only a symbol of maternal care but a powerful instrument for creating new family ties in the region, as noted for the Ayt Atta by Gélard (2010). On the other hand, ambiguous phrasing in the Korandje versions allows for other ways of increasing output; could the couple whose children are to do the herding (7b) be slaves or tenants (both well-established roles in premodern Tabelbala), rather than family members proper? Either way, their labor enriches the protagonist and his family.

But is achieving that enough? The final goal (11b) is the most striking divergence among the stories; no two versions share it precisely. It seems plausible that the final goal in this story was routinely adjusted to fit the preoccupations of the teller and perhaps the circumstances of the telling. In Belaidi’s case, this goal is purely personal: satisfaction of one’s own hunger. (It may be relevant that the narrator was a young man at the time.) In the two Tamazight versions, it is familial—getting another son married in Tahramt, “choking” one’s children with figs in Tiselli. (“Choking” is presumably humorous hyperbole for feeding, possibly from a narrator exasperated with children or researchers asking too many questions.) In all three cases, it amounts to a secular goal rooted in human biology.

The fourth case, however, presents a sharper contrast. Zohra Adda’s goal of anointing the Messenger’s (that is, the Prophet Muhammad’s) locks is rather incongruous in the context of the story—surely the listener is not expected to imagine this homely conversation playing out in seventh-century Mecca? But it amounts to a religious rebuke to the more widespread endings, insisting that the ultimate goal should be to prepare for the afterlife and not just for this world. With this ending in place, the tale comes to echo the well-known Quranic verse 18:46, “Wealth [al-māl, which can also mean ‘livestock’] and children are the attractions of this worldly life, but lasting good works have a better reward with your Lord and give better grounds for hope” (translation by Abdel Haleem (2005:186).

From a more worldly perspective, this ending may also be taken as reinforcing the traditional “sharifian” ideology of Kʷạṛa. Rivalry between the two villages of Kʷạṛa and Ifrenyu, and in particular between the descendants of Sidi Larbi in the former and the Ayt Isful in the latter, has been a prominent part of Tabelbala’s history since the late-nineteenth century (Cancel 1908; Champault 1969). According to Cancel (1908:304), Ifrenyu was founded about 1882 by locally settled descendants of the Ayt Isful as the result of a water ownership dispute with the mṛabṭin (“marabouts,” perhaps better rendered as “saintly families”), who stayed behind in Kʷạṛa, the village both sides had formerly shared. The common patrilineal ancestry of most of Ifrenyu’s inhabitants encourages village-internal solidarity, and formerly provided a basis for claiming external support from other Ayt Atta groups. Kʷạṛa, on the other hand, is inhabited by a wider range of extended families, claiming no single common patrilineal ancestor. The village is physically centered on a graveyard called imạmạḍen (literally, “the marabouts”), dominated by the mausoleums of saints, and regularly visited by those who (unlike modern reformists and Salafists) approve of visiting such tombs. Among the largest of these mausoleums are those of the ancestors of Kʷạṛa’s principal landowners today, described in oral tradition as scholarly, pious traders from the north. Their disputed claim to be descendants of the Prophet Muhammad

11

(that is, sharīfs), entitled as such to all Muslims’ respect and support, has traditionally allowed them to appeal beyond the village, drawing on the widespread “sharifian” ideology (Cornell 1983; Ensel 1999) used to justify traditional class structures in southwestern Algeria and to legitimize the ruling dynasty across the border in Morocco. In the context of such a rivalry, Zohra Adda’s insistence that paying respects to the Prophet is most important is likely to have social/political resonances as well as purely religious ones.

4. Conclusion

The chain tale of the little cat who found money seems to have originated among the Ayt Atta, or at least to have been spread by them. Like any other chain tale, it challenges its listeners to memorize a relatively long list with the aid of loose logical connections; to this, however, it adds an instructive purpose not found in superficially comparable chain tales like The House that Jack Built. Notwithstanding its brevity and its humor, it presents a blueprint for life-planning in the context of traditional life on the fringes of the northwestern Sahara, and even a vision of the ultimate purpose of life which could be adjusted according to the narrator’s own views. No wonder, then, that this tale originally told in Tamazight was deemed interesting enough to be incorporated into the stock of Korandje folktales, surviving even after Tamazight speakers there had shifted to Korandje.

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique

LACITO (CNRS – Sorbonne Nouvelle – INALCO)

Appendix

Here and throughout the paper, words in Tamazight and Korandje are cited in the widely used Amazigh Latin orthography (Chaker 1996), characterized by the following nontrivial correspondences of graphemes (indicated by < >) to phonemes (indicated by slashes and transcribed in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA)): <e> = /ə/, <c> = /ʃ/ (English <sh>), <j> = /ʒ/ (French <j>), <y> = /j/ (English <y>), <ɛ> = /ʕ/ (Arabic `ayn ع), <ḥ> = /ħ/ (Arabic ḥā ح), <ɣ> = /ʁ/ (Arabic ghayn غ), <x> = /χ/ (German <ch>), underdot = pharyngealization (for example, <ṭ> = /tˤ/, Arabic ط). For labiovelarization/rounding, the more transparent IPA form /ʷ/ has been retained in preference to <°>. In addition to these, Korandje—unlike Tamazight—has developed a phonemic distinction between front /a/ (English <a> in cat)and back /ɑ/ (English <a>in father); since many fonts conflate these two IPA characters, back /ɑ/ is transcribed here as <ạ>. False starts are transcribed between curly brackets { }, and proposed emendations between angle brackets < >. Personal names and officially recognized place names are presented in the rather imperfect French-based orthography used by government institutions and by the speakers themselves, without diacritics.

12

Korandje:

| Zohra Adda Kʷạṛa? (Tabelbala) 1950–55 | B. Belaidi Ifrenyu (Tabelbala) December 10, 2007 | |||

| Recording by D. Champault (1950). Accessible with transcription and translation by Souag (see above, footnote 1) | Recording by Souag (unpublished) File name MZ000021 | |||

| 0a | Ɛayḥaja nis ɛaskkat nisi: | I have told you, I haven’t come to you: | ||

| 0b | Icann aḥḥalleq muc fʷ kadda, | God created a little cat. | ||

| 0c | ader aabyinbec. | He went scratching. | ||

| 1a | Affu abbsat aka att as: Tuɣ nbabtellạ? | Someone passed by him and said to him: “What are you looking for?” | ||

| 1b | Tt: ɛa-btella {d} idṛạmen. | He said “I’m looking for money.” | ||

| 2a | Ma nbeɣ idṛạmen? | “What do you want money for?” | Muc kadda muc kadda, tuɣ nbeɣ idṛạmen? | “Little cat, little cat, what do you want money for?” |

| 2b | Ɛemdzay ndzi feṛka. | “So I can buy a donkey with it.” | Ɛbaɛamdzey aka feṛka. | “I want to buy a donkey with it.” |

| 3a | Ma nbeɣ feṛka? | “What do you want a donkey for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ feṛka? | “What do you want a donkey for?” |

| 3b | {Ɛamdza-} Ɛamneggeṛ lạbu. | {So I can put-} “So I can transport clay.” | Ɛbaɛamnegger aka labu. | “I want to carry clay on it.” |

| 4a | Ma nbeɣ labu? | “What do you want clay for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ labu? Tuɣ nbeɣ labu? | “What do you want clay for?” (2x) |

| 4b | Ɛamkạ ạḍḍeb. | “So I can make brick.” | ||

| 5a | Ma nbeɣ ạḍḍeb? | “What do you want brick for?” | ||

| 5b | Ɛamkikey gạ. | “So I can build a house.” | Ɛbaɛammikna aka gạ. | “I want to make a house with it.” |

| 6a | Ma nbeɣ gạ? | “What do you want a house for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ gạ? | “What do you want a house for?” |

| 6b | {Ɛammikna Muḥemmed ndza Fạṭna, immi-} Ɛamdza aka Muḥemmed ndza Fạṭna. | {So I can make Muhammad and Fatna, they will-} “So I can put Muhammad and Fatna in it.” | Ɛbaɛamgwạndza aka Muḥemmed ndza Fạṭna. | “I want to put Muhammad and Fatna in it.” |

13

| 7a | Ma nbeɣ Muḥemmed ndza Fạṭna? | “What do you want Muhammad and Fatna for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ Muḥemmed ndza Fạṭna? | “What do you want Muhammad and Fatna for?” |

| 8b | {Ɛamkikey ɣays ta-} Immisṛeḥ ɣays tawala. | {I will build myself a h-} “So they can herd the herd for me.” | Imsaḥ ɣeys tawala. | “So they can herd the herd for me.” |

| 9a | Ma nbeɣ tawala? | “What do you want a herd for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ tawala? | “What do you want a herd for?” |

| 9b | Ɛamkaw aka huwwa. | “So I can get milk from it.” | Ɛamṣạ{k} ika huwwa. | “So I can [milk] milk from them.” |

| 10a | Ma nbeɣ huwwa? | “What do you want milk for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ huwwa? | “What do you want milk for?” |

| 10b | Ɛamkaw aka gi. | “So I can get ghee from it.” | Ɛbaɛammikna aka gi. | “I want to make ghee out of it.” |

| 11a | Ma nbeɣ gi? | “What do you want ghee for?” | Tuɣ nbeɣ gi? | “What do you want ghee for?” |

| 11b | Ɛamyen ndza Ṛạsuleḷḷạh n tagʷḍḍẹs. | “So I can anoint God’s Messenger’s hair-lock with it.” | Ɛbaɛamɣa. | “I want to eat it.” |

Ayt Atta:

| Rachid Amadin < Lalla Zahra Brahim Taḥramt (Tagounite) January 11, 2012 (Amennou n.d.) | Lhasain ou Mohammed ou Lhasain Rabat < Tiselli (Dades) May 1908 (Biarnay 1912:359) | |||

| 0b | Illa mucc d bnadm, | There was a cat and a human, | ||

| 0c | nnan imrrq mucc | they say the cat crawled | Inkr mucc ar itxabbaṭ iɣd, | A cat started scratching the ashes, |

| 0d | yaf arryal. | and found a riyal. | yaf yan uqqariṭ. | and found a coin. |

| 1a | Inna as bnadm: “Fk iyi t(a)” | The human said: “Give me this.” | Nniɣ as: Ara t id! | I said: “Hand it over!” |

| 1b | Riɣ t! | “I want it!” | ||

| 2a | Inna as mucc: “May t trit?” | The cat said: “What do you want it for?” | Nniɣ as: Ma t trit? | I said: “What do you want it for?” |

| 2b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad is sɣeɣ aɣyul” | The human said: “So I can buy a donkey with it.” | ||

| 3a | Inna as mucc: “May t trit aɣyul?” | The cat said: “What do you want a donkey for?” |

14

| 4b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad is asiɣ uṭṭub” | The human said: “So I can carry brick with it.” | ||

| 5a | Inna as mucc: “May trit uṭṭub?” | The cat said: “What do you want brick for?” | ||

| 5b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad is bnuɣ taḥanut” | The human said: “So I can build a room with it.” | Inna i: Ad <i>s b<nu>ɣ tigmmi inu! | He said: “So I can build my house with it!” |

| 6a | Inna as mucc: “May trit taḥanut?” | The cat said: “What do you want a room for?” | Nniɣ as: Ma tt trit? | I said: “What do you want that for?” |

| 6b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad dis gɣ tislatin” | The human said: “So I can put the brides/daughters-in-law in it.” | ||

| 7a | Inna as mucc: “May trit tislatin?” | The cat said: “What do you want brides/daughters-in-law for?” | ||

| 7b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad iyi ttarwnt arraw” | The man said: “So they can start bearing me children.” | Inna i: Ruḥeɣ a di{r}s tggɣ i<f>rxan inu! | He said: “I’m going to start putting my children in it!” |

| 8a | Inna as mucc: “May trit arraw?” | The cat said: “What do you want children for?” | Nniɣ as: Ma trit arraw nnaɣ? | I said: “What do you want our children for?” |

| 8b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad iyi ikssa iɣjdn” | The man said: “So they can start herding goats for me.” | ||

| 9a | Inna as mucc: “May trit iɣjdn?” | The cat said: “What do you want goats for?” | ||

| 11b | Inna as bnadm: “Ad as gɣ tamɣra i Muḥmmad” | The human said: “So I can arrange a wedding for Muhammad.” | Inna yi: Rix asen akkaɣ tazart tqrjem <t>n akʷ! | He said: “I want to start giving them figs which will choke them all!” |

| 12a | Zriɣ tt nn g ccṛṛ, dduɣ d i lhna! | I left them in misery and came in peace! | ||

| 12b | Iɣss n wadif i imi inu, takurdast imarɣn i ljmaɛt! | The marrow of the bone is for my mouth, and the dirty innards for the gathering! |

15

References

Abdel Haleem 2005

M. A. S. Abdel Haleem. The Qur’an—A New Translation by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem. Corrected ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amaniss 2009

Ali Amaniss. Dictionnaire tamazight-français (parlers du Maroc centrale). Published by the author. https://archive.org/details/aliamanissdictionnairefrancaistamazight/

Amennou n.d.

Abdalla Amennou. Le patrimoine oral des Ayt Atta du Dra. Unpubl. manuscript.

Bellil 2006

Rachid Bellil, ed. and trans. Textes zénètes du Gourara. Documents du Centre national de recherches prehistoriques anthropologiques et historiques, 2. Algiers: CNRPAH.

Ben Maamar 2020

Fathi Ben Maamar. Tinfas seg Jerba—Ḥikāyāt Amāzīghiyyah Jarbiyyah. Paris and Tunis: Ibadica and Paradigme.

Biarnay 1912

Samuel Biarnay. “Six textes en dialecte berbère des Beraber de Dadès.” Journal asiatique, 19:347–71.

Cancel 1908

Cancel (no first name provided). “Étude sur le dialecte de Tabelbala.” Revue africaine, 270–71:302–47.

Chaker 1996

Salem Chaker, ed. Tira n tmaziɣt: Propositions pour la notation usuelle à base latine du berbère. Paris: Centre de Recherche Berbère, INALCO. http://www.centrederechercheberbere.fr/tl_files/doc-pdf/notation.pdf

Champault 1950

Dominique Champault. Collection: Algerie, Tabelbala, missions D. Champault 1950–55. Unpublished audio recordings. Archives sonores du CNRS—Musée de l’Homme. http://archives.crem-cnrs.fr/archives/collections/CNRSMH_I_2003_009/

Champault 1969

______. Une oasis du Sahara nord-occidental, Tabelbala. Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique.

Cornell 1983

Vincent J. Cornell. “The Logic of Analogy and the Role of the Sufi Shaykh in Post-Marinid Morocco.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 15.1:67–93.

Delheure 1989

Jean Delheure. Contes et légendes berbères de Ouargla: Tinfusin. Paris: Boîte à Documents.

16

El-Shamy 2004

Hasan M. El-Shamy. Types of the Folktale in the Arab World: A Demographically Oriented Tale-Type Index. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ensel 1999

Remco Ensel. Saints and Servants in Southern Morocco. Social, Economic, and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia, 67.Leiden: Brill.

Frog 2013

Frog. “Revisiting the Historical-Geographic Method(s).”In Limited Sources, Boundless Possibilities: Textual Scholarship and the Challenges of Oral and Written Texts. Ed. by Karina Lukin, Frog, and Sakari Katajamäki. Special issue of The Retrospective Methods Network Newsletter, 7:18–34.

Gélard 2010

Marie-Luce Gélard. “Les pouvoirs du lait en contexte saharien: ‘Le lait est plus fort que le sang.’” Corps: Revue interdisciplinaire, 1.8:25–31.

Graça da Silva and Tehrani 2016

Sara Graça da Silva and Jamshid Tehrani. “Comparative Phylogenetic Analyses Uncover the Ancient Roots of Indo-European Folktales.” Royal Society Open Science, 3.150645. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150645

Hart 1984

David M. Hart. The Ait ‘Atta of Southern Morocco: Daily Life and Recent History. Cambridge: Middle East and North African Studies Press.

d’Huy 2013

Julien d’Huy. “A Phylogenetic Approach of Mythology and Its Archaeological Consequences.” Rock Art Research, 30.1:115–18.

Kossmann 2000

Maarten G. Kossmann. A Study of Eastern Moroccan Fairy Tales. FF Communications, 274. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

Lafkioui and Merolla 2002

Mena Lafkioui and Daniela Merolla. Contes berbères chaouis de l’Aurès: D’après Gustave Mercier. Berber Studies, 3. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Laoust 1949

Émile Laoust. Contes berbères du Maroc: Textes berbères du groupe Beraber-Chleuh (Maroc central, Haut et Anti-Atlas). Publications de l’Institut des hautes-études marocaines, 50. Paris: Larose.

Lord 1991

Albert Bates Lord. Epic Singers and Oral Tradition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

R Core Team 2018

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rubin 1995

David C. Rubin. Memory in Oral Traditions: The Cognitive Psychology of Epic, Ballads, and Counting-Out Rhymes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

17

Souag 2010

Mostafa Lameen Souag. Grammatical Contact in the Sahara: Arabic, Berber, and Songhay in Tabelbala and Siwa. Ph.D. dissertation, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Souag 2015

______. “Explaining Korandjé: Language Contact, Plantations, and the Trans-Saharan Trade.” Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages,30.2:189–224.

Stroomer 2002

Harry Stroomer. Tashelhiyt Berber Folktales from Tazerwalt (South Morocco): A Linguistic Reanalysis of Hans Stumme’s Tazerwelt Texts with an English Translation. Berber Studies, 4. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Stroomer 2003

______. Tashelhiyt Berber Texts from the Ayt Brayyim, Lakhsas and Guedmioua Region (South Morocco): A Linguistic Reanalysis of Recits, contes et legendes berberes en Tachelhiyt by Arsene Roux with an English Translation. Berber Studies, 5. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Stumme 1900

Hans Stumme. Märchen der Berbern von Tamazratt in Südtunisien. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

Taylor 1933

Archer Taylor.“A Classification of Formula Tales.” Journal of American Folklore,46.179:77–88.

Tillion 1973

Germaine Tillion. “Les deux versants de la parenté berbère.” In Actes du premier congrès d’études des cultures méditerranéennes d’influence arabo-berbère. Algiers: Société nationale d’édition et de diffusion. pp. 43–49.

Uther 2004

Hans-Jörg Uther. The Types of International Folktales: A Classification and Bibliography, Based on the System of Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson. 3 vols. FF Communications, 284–86. Helsinki: Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia.

18